Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati: Chairman of Iran’s Assembly of Experts and Secretary of the Guardian Council

Download PDFPage Navigation

Ahmad Jannati is a 97-year-old ayatollah and politician with close ties to both the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ruhollah Khomeini, and his successor Ali Khamenei, the current Supreme Leader. He has remained an influential player within the complex Iranian political system since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. This resource highlights some of his key posts, starting from his judgeship on the Islamic Revolutionary Court in Ahvaz in the aftermath of the revolution to his current positions as secretary of the Guardian Council and chairman of the Assembly of Experts.

Early Years: Pre-1979 Islamic Revolution

Jannati in his Youth

Jannati in his Youth

Jannati was born in February 1927 in Ladan, a village three kilometers west of Isfahan. He grew up in a poor but pious family. His father, Mullah Hashem, was a well-known cleric, and his mother taught the Quran and other religious texts. There was no school in his hometown, so he traveled to Isfahan to receive his primary education in Arabic literature. He continued his studies at the renowned Qom Seminary where he studied under Islamic scholars such as Ayatollah Boroujerdi, Ayatollah Golpayegani, and the founder of the Islamic Republic Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

From a young age, Jannati expressed aversion to the western influences on Iran that increased during the Shah’s reign. Some sources say that he thought scientific and industrial progress made the Iranian people feel “humiliated and westernized.” Jannati also felt oppressed by what he perceived as the Shah’s anti-Muslim policies. He once said he spent “15 years of [his] life in the time of Rezakhani’s oppression,” a reference to Reza Khan, the first Shah of the House of Pahlavi, given the restrictions on his religious practice. Reza Shah had instituted several policies to curtail the role of Islam in society, chief among which was the kashf-e hijab (“discovery of the veil”) decree, which banned all Islamic veils. Furthermore, religious schools and mosques were often closed and vacant.

In 1947, Jannati married Sediqeh Mazaheri. They had four sons, one of whom became a regime insider and another who joined the People’s Mujahedin Organization of Iran (MEK), a political organization that opposed the Shah, but later clashed with Ayatollah Khomeini over the direction of the Islamic Republic. He went into hiding after the success of the Islamic Revolution, along with his wife, to wage an armed insurgency against the Islamic Republic. Some say he was killed in a confrontation with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in 1981, while others believe he was executed, with his father, a judge at the time, refusing to come to his aid. Ahmad Jannati once said he was “more interested in Islam and the revolution…than the child.” His third son, Mohammad Jannati, works at the Islamic Propaganda Organization, where his father was in charge for decades. And his fourth son, Hassan Jannati, abstained from politics altogether, working as a carpenter in the village where his father was born.

The Haghani School of Thought

After his formative education at the Qom Seminary, Jannati became one of the founders of a prominent Shi’a seminary in Qom, the Haghani Seminary, where he would subsequently teach for fourteen years. Alongside the late Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah Yazdi—who, like Jannati, would rise to become a powerful player after the Islamic Revolution—he created this radical system of beliefs to indoctrinate the next generation of clerical leaders in Iran. Among those beliefs is the idea that an apocalyptic battle will hasten the return of the 12th Imam (“Mahdi”), who will rescue all Shi’a Muslims from evil and create an Islamic state. When seen in the context of Iran’s anti-Americanism and anti-Israel ideology, these millenarian beliefs, shared among supporters of the Supreme Leader, are a dangerous combination.

Jannati’s career as a religious scholar in Qom was shaped by an embrace of the principle of velayat-e faqih (“Guardianship of the Jurist”), which bestows a Supreme Leader with final religious and political authority over all affairs of state. The Supreme Leader, in his view, is not endowed with his power through elections, but rather his religious credentials. This ideology forms the bedrock of the Islamic Republic.

Ahmad Jannati

Ahmad Jannati

Opposition to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

In addition to being a religious scholar, Jannati was a political activist. He organized and participated in many anti-Shah events throughout his career, using his position in the Qom Seminary Teachers’ Association and the Haghani Seminary as a springboard. In 1970, he authored a proclamation, along with eleven other seminary professors, declaring Khomeini’s credentials and eligibility to lead. This was significant because not all Shi’a scholars advocated for religious authorities to be involved in politics. While his teachings were revolutionary, there is debate over whether and to what extent he was part of the so-called militant clergy opposed to the Pahlavi monarchy. In any case, his teachings, and the school he helped create, cultivated leaders of the Islamic Revolution.

Still, he was involved in revolutionary activities, with government officials arresting him on multiple occasions. On his own account, he said “I was threatened, persecuted, and monitored on Khark Island, Rafsanjan, and Qom, and I was arrested several times in Qom. I went to prison three times…for about three months…[and] was once arrested on Khark Island [and] deported to Hamedan for three years.” He is believed to have acted as a sort of messenger for Ayatollah Khomeini, traveling to cities throughout Iran in his capacity as a preacher and religious scholar in order to spread word about Khomeini’s teachings, and, in the process, undermine the then-monarchical system of government. He reportedly maintained close contact with Khomeini to keep abreast of the latest revolutionary activities in key holy cities, such as Qom and Najaf. He planned rallies, wrote speeches and leaflets, and liaised with the centers of power within Khomeini’s movement.

Judge of Islamic Revolutionary Courts

The Islamic Revolutionary Courts were established in the immediate aftermath of the Islamic Revolution in 1979 to hand down judgments in a violent campaign against political dissidents, and former members and supporters of the Shah’s government. Jannati was appointed as a judge in Ahvaz despite his lacking any legal experience. Jannati admitted this himself: “It was decided [by the Supreme Leader] that we’d become judges, and we had zero experience… we weren’t educated in legal studies, we had not studied. But we were familiar with the revolution and Islamic matters.” On countless occasions, he sentenced officials from the Pahlavi government to brutal forms of punishment, stripping them of any right to defend themselves. Over the course of his career as a judge, he presided over revolutionary courts in Ahvaz, Isfahan, Khuzestan, and Tehran.

International Roles and Friday Prayer Imam of Tehran

Ahmad Jannati Preaching

Ahmad Jannati Preaching

In the early years of the Islamic Revolution, Jannati was also named as head of the Islamic Propaganda Organization. He sought to galvanize support for the regime domestically and abroad. For example, he spoke out against student protests that erupted in the early 1980s over the “Cultural Revolution.” In fact, some people hold him responsible for the suppression and killing of student protestors. Jannati also traveled the world to preach and seek Muslim nations’ support for Khomeini’s fatwa calling for the death of author Salman Rushdie for his book “The Satanic Verses.” Later, Jannati would serve as Iran’s Supreme Leader’s representative for Balkan affairs, expanding his international profile.

Supreme Leader Khomeini appointed Jannati to be the Friday Prayer Imam in Ahvaz at the dawn of the Islamic Republic in November 1979. He was appointed to the same position in Qom in 1981 and Tehran in 1992. The Friday Prayer fuses matters of religion and state, and by the time Jannati started leading prayers in Tehran in 1992 he already had years of experience delivering sermons in favor of the Supreme Leader and his domestic and foreign policy agenda. Jannati’s sermons thus shed light on his strong anti-westernism, anti-Americanism, and anti-Israel views, as well as his complete intolerance for political opposition.

Jannati also occupied other roles associated with Friday Prayers, including as head of the provincial Friday Prayer leaders’ committee. He is known for his virulent antipathy toward the U.S. Indeed, he thinks that hostility is a necessary and inherent part of the Islamic Revolution. “We are an anti-American regime…The hostility between us is not a personal matter. It is a matter of principle,” he once said in a televised speech. He has called for Iraqis to take up violence against U.S. forces in Iraq. On numerous occasions, he led crowds in chanting “Death to America.” When the Rouhani administration was negotiating with the U.S., he exclaimed in a sermon: “We say [to the Americans]: come if you are real men… What are the options on our own table? Death to America is the first option on our table.” The crowd proceeded to chant the slogan.

This enmity extends to U.S. partners and allies in the region. For example, Jannati promotes violence and extremism against Israel. In 1991, he called upon the “Islamic world [to support] the real and tangible struggle of the Palestinian people…[who] will stone you.” In 2006, he asserted that support for the extremist group Hezbollah was an Islamic “duty.” During a 2009 sermon, he remarked that he wanted someone to shoot then-Israeli Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni. Jannati has also condemned Saudi Arabia for its campaign against Houthi rebels in Yemen while affirming his support for the Iranian terror proxy. And he said that the Qataris betrayed all Muslims by allowing the Americans to establish the Al Udeid Air Base.

Jannati also uses his sermons to encourage the violent repression of political dissidents. Following the 2009 post-presidential election protests, Jannati called for the arrest of reformist candidates and leaders Mir-Hossein Mousavi, Zahra Rahnavard, and Mehdi Karroubi, and for mass executions of protestors. Jannati publicly thanked then Chief Justice Sadegh Larijani for hanging Mohammad Alireza Zamani and Arash Rahmanipour for their role in the protests, encouraging him to prosecute regime opponents more aggressively. “For the sake of God, persist courageously, just like you executed these two people very quickly…the Qur’an has specified what is to be done with them,” he said in one of his sermons.

In September 2016, when an audio recording of Hosseinali Montazeri speaking out against Khomeini’s decision to massacre thousands of political prisoners in 1988 was leaked, Jannati publicly defended the Supreme Leader. Indoctrinates of the Haghani Seminary, such as President Ebrahim Raisi, are said to have committed these atrocities in the name of the revolution. After 25 years of acting as the Friday prayer leader in Tehran, Jannati resigned, citing old age.

Secretary of the Guardian Council

From left: Ahmad Jannati and Supreme Leader Khamenei

From left: Ahmad Jannati and Supreme Leader Khamenei

The Guardian Council is tasked with screening candidates to run in elections, including the presidential, parliamentary, and Assembly of Experts elections, and ensuring that legislation passed by the Majlis (parliament) coheres with Twelver Shi’a precepts and the Islamic Republic of Iran constitution. Six of the twelve members of the council are experts in Islamic law, appointed by the Supreme Leader, and the other six are jurists confirmed by parliament from a pool of individuals nominated by the chief justice, who is also appointed by the Supreme Leader.

In 1980, one year after the Islamic Revolution, then-Supreme Leader Khomeini appointed Jannati to be one of the six clerics on the council. In July 1992, members of the council elected him to become secretary, and he has served in that role ever since. His extraordinary longevity within the institution owes in part to his obedience to the Supreme Leader. Jannati has made no effort to hide this point, saying that he is “bound to provide…the views of the Supreme Leader,” and has worked to manipulate elections in favor of the system’s desired candidates, often under the Supreme Leader’s guidance.

In 2009, Jannati aided the contested reelection of then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad by presiding over the council’s decisions to disqualify viable reformist candidates. These disqualifications were among the many reasons the Iranian people viewed Ahmadinejad’s reelection as illegitimate, sparking large protests which came to be known as the Green Movement. Jannati took a hardline in response to the protests even as the Supreme Leader asked him and his council to review the opposition’s complaints over the election. Jannati viewed the protestors as seditious, treasonous, and deserving of execution. He also said that any soft treatment of detained political activists would be considered treason.

In February 2020, the month of Iran’s 11th parliamentary election, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Jannati, along with other Guardian Council members, for “depriving the Iranian people of free and fair elections by blocking candidates that do not mirror [the Supreme Leader’s] radical views.” The Treasury Department’s press release noted that Jannati oversaw the disqualification of nearly half of the potential parliamentary candidates, including several incumbent legislators.

The 2021 presidential election was plagued by the same manipulation of the candidate field, with over 3,000 potential candidates barred from running, including the former speaker of parliament, Ali Larijani. These mass disqualifications were partly in response to a letter written by Jannati that declared that, according to Sharia law, non-Muslims could not run in Shi’a Muslim-majority areas in city and village council elections. As a result of the push to eliminate leading reformist candidates, the election saw some of the lowest voter turnout in the history of Iranian elections.

Jannati also played a key role in the effort to disqualify Ali Larijani—a former speaker of parliament, former secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, and former minister of culture and Islamic guidance in the Rafsanjani administration. His brother, Sadegh Larijani, was the chief justice of Iran from 2009 to 2019, and currently serves as chairman of Iran’s Expediency Council. Sadegh Larijani was also a member of the Guardian Council until September 2021, when he resigned from his position because the council disqualified his brother from running for president.

Despite his influence, Sadegh Larijani was unable to protect his brother against the machinations of the Guardian Council to purge the candidate field of pragmatists. Specifically, Jannati wrote a letter to Ali Larijani disqualifying him because of his “political positions and statements” regarding the protests following the 2009 election, his support for disqualified candidates, his daughter’s reported residency in Ohio, his positive views of the nuclear deal, and his lack of “biological simplicity.”

A Tehran-based Iran analyst noted that “almost all of the accepted candidates [in the 2021 election were] less likely to compete with Raisi,” and thus, the council “ended the election before it started.” Iranian voters were limited to choose from candidates that were deemed acceptable and desirable by the establishment. Under Jannati’s leadership, Rouhani's allies were largely rejected, and thus the presidential election was paved for the victory of Ebrahim Raisi.

With Jannati at the helm, the Guardian Council’s mandate to ensure that candidates are qualified to run in elections means eliminating hopefuls viewed as not sufficiently hardline and loyal to the Supreme Leader. Likewise, its second mandate—approving or rejecting parliamentary legislation on the basis of whether or not it coheres with Islamic law and the Iranian constitution—has on some occasions resulted in the rejection of more moderate bills. For example, the Guardian Council rejected legislation that would have allowed minority non-Muslims to run in local elections. It vetoed a law, supported by the Rouhani administration, that would have banned terror financing, with some arguing against limits on the regime’s ability to fund “resistance groups” such as Hezbollah and Hamas.

In July 2023, Khamenei again reappointed Jannati as the Guardian Council’s secretary, positioning him to purge the candidate field of politicians unaligned with Khamenei’s hardline vision ahead of the 2024 parliamentary elections.

Chairman of the Assembly of Experts

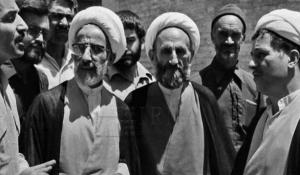

From left: Mohammad Ali Rajaee, Ahmad Jannati, Abulqasem Khazali, and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

From left: Mohammad Ali Rajaee, Ahmad Jannati, Abulqasem Khazali, and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

The Assembly of Experts is an 88-member body tasked with selecting the Supreme Leader and overseeing his conduct. In practice, however, the Supreme Leader is unaccountable and has the final say over all matters of state. In fact, the Assembly of Experts often takes its cues from the Office of the Supreme Leader. Jannati once made this point explicit, saying, “the Assembly of Experts must support the Supreme Leader regularly and continuously to help him establish his authority.” Given that the Assembly of Experts members are elected from a heavily-vetted shortlist of eligible candidates, they act at the Supreme Leader’s discretion rather than as an obstacle to his rule. Their loyalty ensures the continuation of Khamenei’s hardline legacy after he passes. Jannati has been a member of the Assembly of Experts since 1983, first representing Khuzestan until 1998 and later Tehran.

In 1989, following the death of Supreme Leader Khomeini, the Assembly of Experts had to select a new Supreme Leader. The candidates to succeed Khomeini ranged from Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani to Khomeini’s son, Ahmad. A debate ensued about whether the Islamic Republic should establish a council to rule in place of a single Supreme Leader. Jannati gave an influential speech in the Assembly of Experts, contending that individual leadership was preferable to council leadership because it would not be subject to discord. The speech, alongside Rafsanjani’s lobbying, was instrumental in the assembly’s decision to select Khamenei as the next Supreme Leader.

Members of the Assembly of Experts are Mujtahids (Islamic theologians), elected to eight-year terms through popular vote, although candidates have to be vetted by the Guardian Council before they can stand for election. Members of the assembly then elect the chairman. Jannati first ran for the chairmanship in 2007, but he lost to former president Rafsanjani, a pragmatist who, despite lobbying in favor of Supreme Leader Khamenei in 1989, has advocated for collective leadership instead of a single Supreme Leader. While elections for the Assembly of Experts are held every eight years, members of the assembly cast their votes to select a chairman every two years. Jannati lost the election for the chairmanship in 2007. His fortunes changed in 2016.

The February 2016 Assembly of Experts elections was a major victory for more moderate politicians, and the ticket backed by Rafsanjani gained 52 of the council’s 88 seats. However, despite this success, the members of the Assembly of Experts elected Jannati to be chairman with 51 votes out of 86 votes. Rafsanjani failed to gather the support to mount a challenge and threw his weight behind Ebrahim Amini, who won 21 votes. Former Chief Justice Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, a conservative, also ran for chairman; he won 13 votes. Somewhat surprisingly, Rafsanjani downplayed the importance of the internal vote just days before the vote was to take place, saying, “it makes no difference whether to be a member or the chairman. The assembly doesn’t have many activities and only holds two sessions a year.” Contrary to this statement, though, the chairman manages the assembly’s internal decision-making process, regularly liaises with the Supreme Leader, and supervises all administrative, financial, organizational, and employment affairs of the assembly. The losses of the 92-year-old moderate Amini and Shahroudi indicated that the hardline conservative members of the assembly still had the upper hand.

Before the vote for the chairmanship, the Supreme Leader called on the assembly to affirm its “revolutionary” character. His wishes for the quasi-elected body were clearly met, given the political mobilization behind Jannati. Meddling from the Office of the Supreme Leader also took place as Iran’s Supreme Leader’s intelligence and security advisor, Asghar Mir-Hejazi, reportedly intervened to pave the way for Jannati’s chairmanship. In line with the Supreme Leader’s wishes, many moderates in the assembly then voted for Jannati. The outcome showed that a group of hardliners, with the backing of the Supreme Leader, still wielded outsize influence within both the Guardian Council and the Assembly of Experts, despite a newly-inked nuclear deal, which some observers hoped would lead to moderation in Iranian politics. Jannati’s election to the assembly chairmanship also showed his influence as secretary of the Guardian Council, as he helped screen out potential candidates for the assembly that could have voted against him for chairman.

As chairman of the Assembly of Experts, Jannati injects his opinion into political debates, especially regarding the repression of dissent and foreign policy. For example, Jannati advocates for the “resistance economy,” a phrase coined by Supreme Leader Khamenei to encapsulate efforts to circumvent international sanctions instead of sanctions relief through international accords. He even called on then-President Rouhani to apologize to the people of Iran for ignoring the Supreme Leader’s wishes about the nuclear deal negotiation. In doing so, he was attempting to remove blame for the failed nuclear deal and floundering economy from the Supreme Leader and displace it onto Rouhani. In response to these accusatory statements, the outspoken then-Deputy Speaker of Parliament from Tehran, Ali Motahari, stepped in to defend Rouhani’s government, arguing that the “Assembly of Experts has no legal right to interfere in cases such as the JCPOA or to set agendas for the president or parliament.”

In another foray into politics, Jannati issued a statement that strongly rejected any criticism directed at Supreme Leader Khamenei. He said, “Denying the guardianship of the Supreme Leader is the same as denying God.” By likening the Supreme Leader to God, he laid the groundwork to punish protestors and dissidents as though they had committed apostasy. This declaration further demonstrates Jannati’s steadfast loyalty to the Supreme Leader and his unwavering conviction to the core precept of velayat-e faqih.

When protests in Iran broke out in September 2022 after the death of a young woman in custody, the Assembly of Experts issued a letter stating that the protests were seditious and orchestrated by foreign powers. The letter, signed by Jannati, called for adherence to and strict enforcement of Sharia law and expressed support for the IRGC’s ballistic missile strikes against Iraqi Kurdistan, where Iran claims Kurdish groups opposed to the Islamic Republic are based. Religious rules, such as the hijab mandate, have been a focal point of the protest movement.

In February 2023, members of the Assembly of Experts reelected Ayatollah Jannati as chairman of the body. After the elections, Jannati published an open letter on behalf of the Assembly of Experts full of obsequious commentary and praise for the Supreme Leader. For example, the letter noted how Khamenei provides for “solidarity and national unity” and the “guidance and management of society.”

Other Leadership Positions

Member of the Expediency Council

Jannati has been a member of the Expediency Council since 1997. There is not much publicly-available information on his role there. The council is an advisory board for the Supreme Leader that settles disputes over legislation between Iran’s Guardian Council and the parliament. As noted, the Guardian Council can reject parliamentary legislation if it is deemed contrary to Islamic teachings or the Islamic Republic of Iran’s constitution. In many circumstances, the Guardian Council determines whether legislation passes into law. However, if the Guardian Council disapproves of a bill passed in parliament, parliament can elect—with a two-thirds majority—to send the legislation to the Expediency Council, which then decides on the final form of the bill. As a member of this council, Jannati has further power to ensure that his decisions in the Guardian Council have ample impact on the law.

Prospects to Succeed Jannati

Ahmad Jannati (Left) pictured with Former President Hassan Rouhani (Right)

Ahmad Jannati (Left) pictured with Former President Hassan Rouhani (Right)

With a conservative majority under Jannati’s leadership in the Assembly of Experts and President Ebrahim Raisi serving as its first deputy chairman, it remains likely that the next Supreme Leader will be selected based on his long-standing commitment to the aging current Supreme Leader. Earlier in his career, Jannati might have been considered a possible successor to the Supreme Leader. However, at 95 years old, Jannati’s longevity is uncertain. It is likely that the Islamic Republic will want its third Supreme Leader to serve for at least a decade, as did Ruhollah Khomeini from 1979-89. Thus, it is highly unlikely that Jannati will be considered for the position. A younger generation of clerics in the Islamic Republic’s establishment, including Ebrahim Raisi, Mojtaba Khamenei, and Alireza Arafi, are more probable contenders for the Supreme Leadership.

Ahmad Khatami, a prospect to become the next Supreme Leader, may be a contender to succeed Jannati as chairman of the Assembly of Experts. He first became a member of the Assembly of Experts in 1999, and he won a leadership role in the assembly in 2016, as secretary of its board of directors. Like Jannati, he is also a member of the Guardian Council. Former chief justice Sadegh Larijani may be another option to succeed Jannati as chairman, as former chief justices like Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi and Mohammad Yazdi have served in the role.

Ahmad Khatami is also a potential contender to succeed Jannati as Secretary of the Guardian Council. He maintains a similar worldview as Jannati, as he is a principlist. For example, he characterized protesters demonstrating against the contested 2009 presidential election as waging war against God, a crime punishable by death in Islamic law. If Khatami became secretary of the Guardian Council, he would have more leverage over its deliberations on who is permitted to run for election to the Assembly of Experts. Therefore, like Jannati, he would influence the body in which he stands to run for chairman. But Khatami would undergo competition within the Guardian Council from other potential candidates, including Ayatollah Alireza Arafi and Mohammad-Reza Modarresi Yazdi.

Ayatollah Arafi’s academic and religious roles within the regime support his candidacy for this position. He has occupied key Friday Prayer leadership positions, along with high-level appointments such as membership on the Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution, the head of Islamic Seminaries of Iran, and chairman and former president of Al-Mustafa International University. On the other hand, Ayatollah Arafi lacks political experience. He lost an election for a seat on the Assembly of Experts in 2016.

Finally, Mohammad-Reza Modarresi Yazdi can be viewed as a possible successor to Jannati in the Guardian Council, given his close ties to Supreme Leader Khamenei. He was appointed and reappointed to the Guardian Council, though he too lost the election to become member of the Assembly of Experts in 2016, and his name was on the shortlist to succeed Sadegh Larijani as judiciary chief, a position appointed by the Supreme Leader. Ahmad Khatami, Ayatollah Arafi, and Mohammad-Reza Modarresi Yazdi are names to watch as possible successors to Jannati for the top leadership position in the Guardian Council.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Iranian system is designed to enable the Supreme Leader to maintain control over all matters of state, including his own succession. Jannati’s leadership positions, leveraged to the benefit of the Supreme Leader, are a result of this design. There is no surprise that Jannati holds positions of such power, given that he believes a practical commitment to Islam entails pure and unquestioning obedience to the Supreme Leader. His calls for violence against protestors, and pragmatic candidates, and his virulent anti-Americanism and anti-Israel views, can be understood in this context. It remains probable that the next secretary of the Guardian Council and chairman of the Assembly of Experts will hold similar perspectives on the repression of domestic dissent, and the expansion of the revolution abroad, with the final goal of preserving the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox

The Iran nuclear deal is done. And the world's biggest companies have already visited Tehran ready to strike a deal when sanctions end. These businesses will add even more to Iran's bottom line. And that means continued development of nuclear technologies and more cash for Hamas and Hezbollah.