Cruel and Inhuman: Executions and Other Barbarities in Iran’s Judicial System

Download PDFPage Navigation

Iran’s judicial system remains among the most brutal in the world. The Iranian regime executes more people per capita than any other country. It carries out more total executions than any nation but China, whose population is over 17 times that of Iran’s. Tehran continues to target political dissidents and ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities for execution. Capital punishment can be—and often is—carried out against juvenile offenders and for nonviolent crimes.

The cruelty and inhumanity of Iran’s judicial system goes well beyond executions, however. Individuals may be arrested and indefinitely detained without charge or on trumped-up offenses; subject to degrading treatment, including torture, in order to extract confessions; denied rights such as access to legal counsel and fair and speedy trial; and sentenced to other barbaric penalties such as amputation, blinding, and flogging.

Those accused and/or convicted of perpetrating crimes are incarcerated in overcrowded prisons where they may be subject to torture, rape, and other atrocities. Iran’s densely populated and dirty penitentiaries are also breeding grounds for the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and other illnesses, and prisoners are often denied necessary medical care (including COVID-19 tests), personal protective equipment, and disinfectant.

Here are some facts and figures on the use and abuse of executions and other barbarities by Iran’s judicial system.

Executions

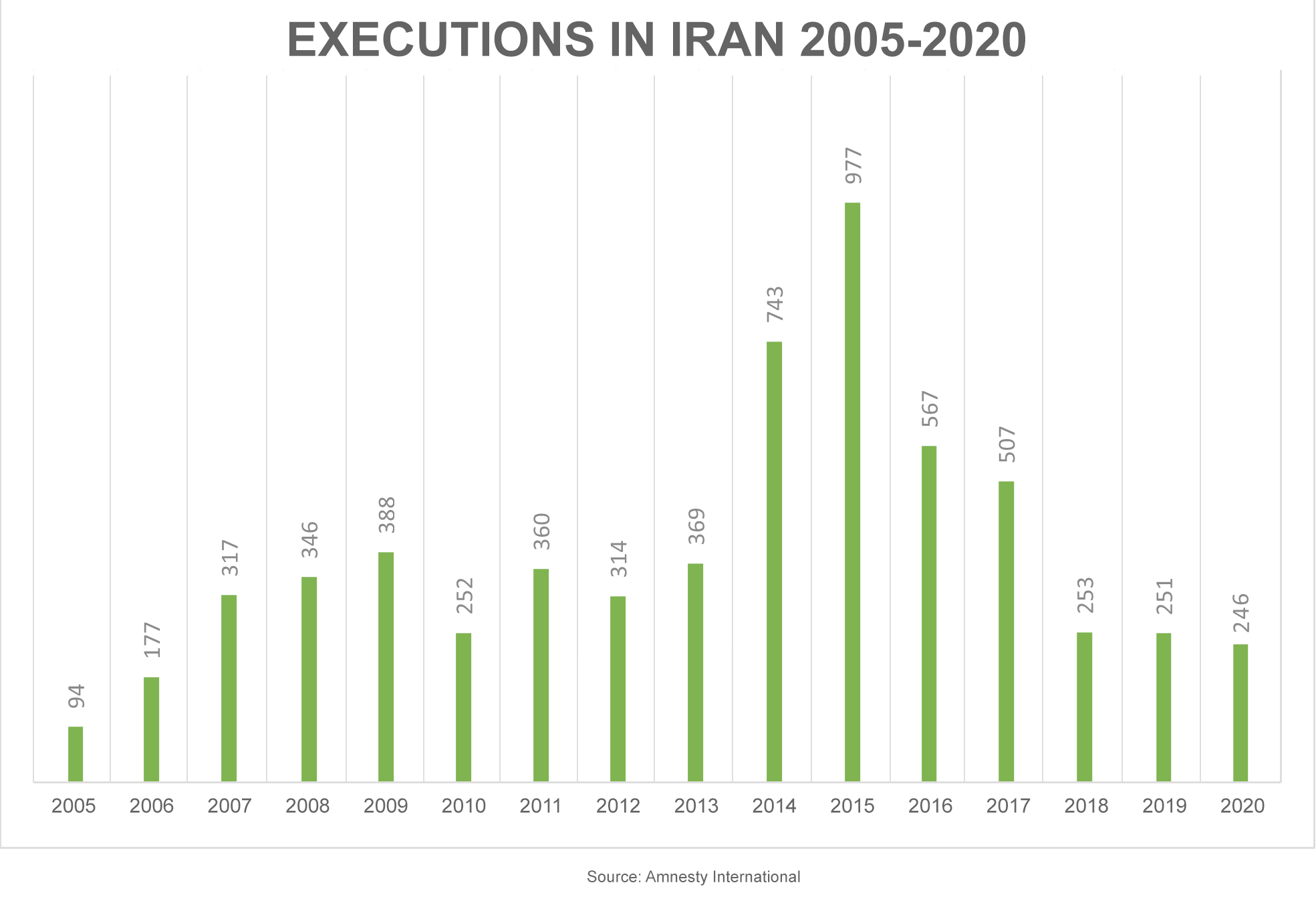

Executions in Iran by the Numbers

2021 Execution Figures

Amnesty International has yet to release its figure for the number of executions in Iran in 2021. However, Javaid Rehman, United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Iran, reported to the U.N. Human Rights Council that Iran executed at least 275 people in 2021. These include at least 2 child offenders and 10 women. Further, executions for drug crimes in 2021 more than tripled from 2020, going from 25 to more than 80. Executions of minorities, including Kurds and Baluchis, also increased.

Methods of Execution

Iran executes the majority of convicts by hanging within prisons. The regime, however, also regularly carries out executions in public, including at least 13 in 2019. In many of these cases, the victim is publicly hanged from a construction crane, an especially slow and painful execution method.

Stoning also continues to be a state-sanctioned form of execution. Other legal methods of execution include firing squad, beheading, and being thrown from a height.

Execution of Protestor and Champion Wrestler Navid Afkari

The Iranian regime hanged champion wrestler Navid Afkari on September 12, 2020, in Iran’s most prominent execution in years. Afkari was convicted of and sentenced for purportedly murdering a security guard during widespread public protests in 2018. He was 26 or 27 years old when executed.

Shiraz’s Criminal Court condemned Afkari to death, as well as one year in prison and 74 lashes, for “participation in illegal demonstration and disrupting public order,” and three-and-a-half years for “disobeying a law enforcement officer’s order and insulting him.” The city’s Islamic Revolutionary Court, which hears cases based on political “crimes,” sentenced Afkari to death for death on the charge of moharebeh (“waging war against God”) and two years in prison for insulting Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. His trials were held in secret.

Afkari claimed that the authorities tortured him into confessing to the crime, including by beating him with a baton and choking him by covering his head with a plastic bag until he almost suffocated. Iranian state television aired his confession on September 5, one week before his execution.

Shortly before Afkari’s death, a recorded message from him was released. "If I am executed, I want you to know that an innocent person, even though he tried and fought with all his strength to be heard, was executed,” he said.

Afkari’s defenders, including the U.S. Department of State, argue that the regime executed him for simply participating in the protests. Reportedly, the government responded to the demonstrations with brutal repression, including by arresting thousands of protesters and flogging, sexually abusing, and otherwise torturing many of them. Iran has long waged war on protesters, including through both extrajudicial killings and death sentences for trumped-up charges

Execution of Exiled Activist Ruhollah Zam

The Iranian government executed Iranian activist and former journalist Ruhollah Zam on December 12, 2020. Zam lived in exile with refugee status in France and openly sought the overthrow of the Islamic Republic. He ran Telegram channels to spread information to Iranians protesting the regime and encouraged viewers to join demonstrations. Zam’s channels—particularly AmadNews—disseminated times and places of upcoming rallies to its subscribers, who numbered more than a million. He also published controversial materials undermining the regime, including documents revealing government corruption and malfeasance.

In mid-October of 2019, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) announced that it had arrested Zam after he was “guided into the country” via a “complicated intelligence operation,” adding that Zam had “stepped into intelligence trap of the Guards some two years ago.” The IRGC posted news of Zam’s arrest on his Telegram channel, as well as a photo of Zam in captivity, with the caption “This is just the beginning.”

The IRGC claimed Zam was being guided and safeguarded by American, Israeli, and French intelligence agencies, and called him “one of the main people of the enemy’s media network and psychological warfare.” A senior IRGC general said, “Zam was a key figure of intelligence services for throwing the country into disarray… and driving a wedge between the Iranian people and government.” On October 23, 2019, an IRGC spokesperson claimed that the Guards had “already captured many of [Zam’s] contacts inside the country.” Media and others tied to the IRGC have said that finding Zam’s network of sources is more important than capturing the activist himself.

The regime forced Zam to confess on Iranian television to engaging in “counter-revolutionary” actions in France's direction. He apologized to the Islamic Republic, said he regretted “what has happened in the past three or four years,” and stated that he was “wrong” to trust foreign governments like France’s, and “especially governments that show they do not have good relations with the Islamic Republic," including the United States, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.

Zam’s trial began on February 10, 2020, in Tehran’s Revolutionary Court. Zam was reportedly charged with either 15 or 17 counts, including “sowing corruption on earth,” insulting “the sanctity of Islam,” and “conspiring with the US Government against the Islamic Republic of Iran”—all of which carry the death penalty—as well as having “committed offences against the country's internal and external security,” “complicity in provoking and luring people into war and slaughter,” “espionage for the French intelligence service,” “spying for Israeli intelligence services via the intelligence services of one of the countries in the region,” “establishment and administration of the Amad News channel and the Voice of People,” and “insulting Ruhollah Khomeini and Ali Khamenei.”

An Iranian judiciary spokesman announced on June 30, 2020, that Zam had been convicted and sentenced to death for 13 counts, which were grouped together and treated as cases of “sowing corruption on earth.” He was also sentenced to life in prison for “several other charges,” which were unnamed. On December 10, 2020, an Iranian court upheld the death sentence against Zam.

Execution of Child Offender Arman Abdolali

Iran hanged child offender Arman Abdolali on November 24, 2021, after having his execution rescheduled six times in the prior two months. At age 17, Abdolali was arrested for allegedly murdering his missing girlfriend, whose body was never located. He was convicted in 2015 and sentenced to death. Abdolali claims that he was beaten into “confessing” and that he was held in solitary confinement for 76 days and denied medication for his asthma. He was 25 when executed.

International human rights officials objected prior to Abdolali’s execution. “Iran must halt the execution of Mr. Abdolali and unconditionally abolish the sentencing of children to death,” said United Nations experts on human rights in Iran, children’s rights, misuse of the death penalty, and torture. “It must commute of all death sentences issued against these individuals, in line with its international obligations.” Germany’s human rights commissioner said that executing Abdolali would constitute an “unacceptable breach of international law.”

After the execution, a spokesman for the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights called it “deeply alarming and shocking,” while European Union and British foreign ministry spokespersons “condemn[ed]” it “in the strongest terms.”

In an interview three weeks before being put to death, Abdolali spoke about the psychological toll of being threatened repeatedly with imminent execution:

Usually they transfer you for execution a day or two before the scheduled date. You’re cut off from everyone. You think that you won’t be alive in a day or two, or even in a few hours. Even today, I think I’m supposed to be transferred for execution again and I don’t know if I’ll be executed tomorrow or not. I’ve been transferred to solitary confinement in preparation for my execution five times. And once two years ago. They even took me to the gallows but officials were able to gain an extension from [his alleged victim’s parents] moment before the execution was carried out. Every time I’m transferred for execution, I think it will be my last time.

Recent Executions of Ethnic Minorities

In late 2020 and early 2021, the regime executed a slew of political prisoners from the Ahwazi Arab and Balochi ethnic minority communities in Iran. Most Ahwazi Arabs reside in the Iranian province of Khuzestan, while most Balochis live in the Balochistan region, which makes up parts of Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

On February 28, the authorities killed four Ahvazi Arabs: Jasem Heidary, Hossein Silawi, Ali Khasraji, and Nasser Khafajian. The regime provided zero notice in advance to the families of those executed. Relatives were brought to the prison and permitted to visit their imprisoned kin for 20 minutes. The relatives were then told to wait, and 30 minutes later—again, with zero notice—they were brought the bodies of their loved ones.

The regime accused Silawi, Khafajian, and Khasraji of attacking a police station in 2017 and killing two police officers. The three were denied access to relatives and legal counsel. They were tortured—including by being beaten and having their ribs or hands broken, and being placed in extended solitary confinement—into “confessing” to crimes, and they were sentenced to death on the basis of those coerced confessions. The three were transported to an undisclosed location for months.

Heidary was charged with “armed insurrection.” He likewise was tortured, including by being thrown into solitary confinement for months, and sentenced to death for purportedly working with anti-regime organizations.

The Iranian government has also executed at least 21 Baluchis from December of 2020 to February of 2021. Among those killed was Javid Dehghan, whom the regime hanged on January 30. He was charged with being part of an armed group and an attack that killed two of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps members. As with other prisoners, his captors tortured Dehghan into “confessing” and he was sentenced to death.

In December 2021, Iranian authorities secretly executed Iranian Kurdish prisoner Heidar Ghorbani at Sanandaj Central Prison without prior notice to his family or lawyer. U.N. experts condemned the episode, saying “the Islamic Republic of Iran executed Mr. Ghorbani in secret, on the basis of overbroad provisions, following a deeply flawed process, and while his case was still under consideration by the Supreme Court.” Ghorbani was arrested in October 2016 in connection with the killing of three members of the Basij. Despite a revolutionary court finding Ghorbani was unarmed, it still sentenced him to death.

Other Evils in Iran’s Judicial System

Severe Forms of Punishment besides Execution

Extreme methods of punishment in Iran other than the death penalty include amputation, blinding, and flogging.

Jailing of Political Prisoners

Iran incarcerates an estimated 625 known political prisoners and members of ethnic and religious minority communities as of March 4, 2021, according to the Iran Prison Atlas of the NGO United for Iran. Such prisoners include:

| Religious and ethnic minorities | Lawyers |

| Human rights activists | Trade unionists |

| Women's rights activists | Writers |

| Civic Activists | Artists |

| Journalists | Social media activists |

| Bloggers | Other dissidents |

Political prisoners are often sentenced to death and executed on trumped-up, nonpolitical charges, including drug smuggling. Consequently, the true number of political prisoners incarcerated or executed remains unknown.

Trampling on the Legal Rights of the Accused

The Iranian government frequently violates the legal rights of the accused by denying them:

- Prompt information about the charges against them;

- Access to an attorney, or the ability to select an attorney of one's choice (instead of one from a pool of lawyers chosen by the head of the judiciary);

- Fair, speedy, and public trial by an independent court; and

- The provision of information to their family about the charges against them.

Torture and Other Degrading Treatment of the Accused

Those arrested or otherwise detained in Iran face appalling treatment—often to coerce confessions—including:

| Sleep deprivation | Blindfolding during interrogations |

| Denial of medical treatment | Arrest, detention, and torture (often in earshot of the accused) of family members |

In one egregious case, the Center for Human Rights in Iran revealed in October 2021 that Payman Derafshan, a former chairman of the Iranian Bar Association's Lawyers' Defense Committee, bit off a part of his tongue after being forcibly given a mysterious injection that caused seizures while being in the custody of the IRGC's Intelligence Organization.

What’s a Crime in Iran?

Iran violates its citizens' human rights by arresting, detaining, imprisoning, and often executing them for “crimes” often committed merely by exercising fundamental freedoms. Many of these offenses are vaguely defined and can thus be exploited for arbitrary detention and punishment. Such crimes include (those punishable by execution are marked with an asterisk):

|

|

Barbaric Conditions Inside Iran's Prisons

Those incarcerated in Iranian prisons are subject to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, including:

|

|

COVID-19

COVID-19 has ravaged Iran. As of March 30, 2022, Iran has had more than 7 million cases of the virus and more than 140,000 deaths, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 Dashboard. The virus has hit prisoners particularly hard because of the aforementioned overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and denial of health care. High-ranking prison-system officials have repeatedly complained to the health ministry about having insufficient disinfectants, personal protective equipment, and essential medical devices but have received no publicly reported response.

In February 2020, the authorities temporarily furloughed a reported 120,000 some-odd prisoners, presumably to reduce the population density in its prisons and minimize the virus's spread. However, most political prisoners were not released, and according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the regime has ordered “large numbers” of those furloughed to go back to prison.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox

The Iran nuclear deal is done. And the world's biggest companies have already visited Tehran ready to strike a deal when sanctions end. These businesses will add even more to Iran's bottom line. And that means continued development of nuclear technologies and more cash for Hamas and Hezbollah.