Organizational Chart of the Islamic Republic of Iran

The Judiciary

Article 156 of Iran’s constitution defines the judiciary as an “independent power,” which investigates and passes judgment on grievances, violations of rights, complaints, resolves litigation, settles disputes, and takes all necessary decisions and measures in probate matters. It also supervises the proper enforcement of laws and “uncovers crimes, prosecuting, punishing, and chastising criminals; and enacting the penalties and provisions of the Islamic penal code.” As the United Nations (UN) special rapporteur for human rights in Iran has noted, “the judiciary plays a vital role in interpreting often vaguely defined national security laws. However, this role can only be undertaken effectively if the rules for the appointment of members of the judiciary are transparent and based on the criteria of competence and integrity. It has been widely reported that strong interference is exerted regarding the appointment of judges. The Iranian judiciary has parallel systems: the public courts have general jurisdiction over all disputes, while the specialized courts, such as revolutionary courts, military courts, special clerical courts, the high tribunal for judicial discipline, and the court of administrative justice have functional areas of specialization.”

Iran’s supreme leader directly appoints a chief justice for a period of five years, and the chief justice is considered the highest judicial authority. The chief justice, according to Article 162, also nominates the chief of the Supreme Court; the prosecutor-general for a period of five years; as well as six constitutional law experts who serve on the Guardian Council. Separately, the chief justice serves as a standing member of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), which calls into question the constitution’s description of the judiciary as a truly “independent power.”

Iran’s judiciary is one of the most feared and notorious institutions in the Islamic Republic. Draconian sentences—from executions to floggings—coupled with the absence of due process have plagued the system for decades. During the tenure of Chief Justice Mohammad Yazdi from 1989-1999, he abolished the Office of the Prosecutor, which resulted in judges doubling as prosecutors, and in the process, denied a fair trial to the accused. Although his successor, Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi later undertook reforms, complaining that he inherited an institution in “ruins,” since 1989, every chief justice of Iran has been sanctioned by the U.S. government for wide-ranging abuses. The UN special rapporteur for human rights in Iran warned in 2021, “the structural flaws of the justice system are so deep and at odds with the notion of the rule of law that one can barely speak of a justice system.”

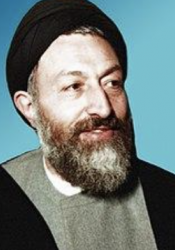

The chief justice of Iran has traditionally been a leading figure in the Iranian system. Before he was killed in 1981, Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti, then head of the State Supreme Court, was considered by some to be the second most powerful figure in Iran after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Since 1989, observers have considered almost every chief justice as a top contender to succeed Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as supreme leader. Before their careers as chief justices, some served on the Guardian Council—for example Yazdi, Shahroudi, and Sadegh Larijani, who also served on the Assembly of Experts before becoming chief justice in 2009. Others, like Yazdi, had parliamentary experience as well. More recently, Ebrahim Raisi spent years climbing through the ranks of the judiciary—as a Tehran prosecutor-general, head of the General Inspection Office, deputy chief justice, and attorney general. Gholamhossein Mohseni-Ejei, the current chief justice, also had a similar career trajectory, climbing the ranks of the judicial and intelligence communities—serving as intelligence minister, attorney general, and deputy chief justice—before securing the seat at the helm of the judiciary.