Candidates for Speaker of Iran’s Parliament

Ali Larijani, the longest-serving speaker of parliament in the history of the Islamic Republic of Iran, concluded his tenure this week. New members of parliament were sworn during its inaugural session on May 27. An interim speaker and deputy speaker now preside over the legislative chamber until their permanent replacements are selected.

Parliament’s authority has eroded in recent years. The institution of a new gas policy in 2019, which circumvented the legislative chamber, is one such example. Nevertheless, being an MP has, at times, proved to be a career-making steppingstone in Iran, with former legislators going on to serve as cabinet ministers and even presidents. As in many countries, it provides a platform and visibility within Iran’s elected state. For instance, Hassan Rouhani was an MP during his ascension to the top ranks of the Islamic Republic. The reverse is true as well. Some cabinet ministers and even vice presidents have chosen to run for the legislature after their tenures in the top levels of government ended —for instance, outgoing Deputy Speaker Masoud Pezeshkian previously served as health minister, and Mohammad Reza Aref was the first vice president in the Khatami administration before long careers in parliament.

Competition for the speakership position is fierce. Former speakers included Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who was very close to Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini. The top parliamentary job is also coveted because it has seats on the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and the Supreme Economic Coordination Council.

Conservatives prevailed in February’s parliamentary elections by large margins, specifically 221 out of 290 seats. This was the result of record-low turnout overall and a conservative base energized after years of Rouhani’s pragmatic brand of politics. However, it would be a mistake to view this result as a sign of unity among conservative factions. Multiple conservative contenders for the speakership have emerged spanning the spectrum of Tehran’s conservative factions. As media reports have outlined, some of the groupings include neoconservatives, traditional conservatives, pro-Ahmadinejad factions, and the Paydari Front. Below are brief profiles of some of the leading contenders for speaker of Iran’s parliament.

Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf: Ghalibaf leads the neoconservative faction in Iran’s new parliament. A longtime fixture of the regime, Ghalibaf has a revolutionary and technocratic pedigree. He commanded two organs of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). From 1994-97, he was the head of the Khatam al-Anbia Construction Headquarters during a period of rebuilding after the Iran-Iraq War. Later, Ghalibaf became the commander of the IRGC-Air Force from 1997-2000. During his tenure, Ghalibaf signed onto a letter in July 1999 alongside other IRGC commanders, warning then reformist President Mohammad Khatami over continuing student protests and pressuring him to stem the unrest. Later, Ghalibaf became Iran’s chief of police, or the Law Enforcement Force of the Islamic Republic of Iran (LEF). While the LEF nominally reports to Iran’s government through the Interior Ministry, Iran’s supreme leader oversees its operations. Ghalibaf’s selection was important as his predecessor Hedayat Lotfian was ousted following the student protests, and it was a signal of Khamenei’s confidence in Ghalibaf to professionalize the LEF during a sensitive period in the Islamic Republic. It was also a check on Khatami during his second term, as Ghalibaf was one of the original signatories to the aforementioned July 1999 public letter. A tape later emerged of Ghalibaf bragging to the Basij how he ordered police to fire at student demonstrators in 2003.

After his tenure at the helm of the LEF, Ghalibaf entered Iran’s political scene, running for the presidency in 2005. Leaked U.S. government diplomatic cables reveal speculation that the supreme leader’s son, Mojtaba Khamenei, was the “backbone” of Ghalibaf’s political campaigns. During the 2005 campaign, Iran’s former speaker of parliament, Mehdi Karroubi, alleged that Mojtaba Khamenei persuaded his father to shift his support to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, then mayor of Tehran, because he was more reliable than Ghalibaf. Ghalibaf lost that race, but soon after took over as mayor of Tehran after Ahmadinejad won the presidency, potentially viewing the position as a platform to pursue higher office after Ahmadinejad’s victory. Ghalibaf’s mayoral tenure was defined by infrastructural feats, including the expansion of the Tehran metro and the Sadr expressway as well as the establishment of new green spaces within Tehran. But his tenure was damaged by a deadly fire, which resulted in the collapse of Tehran’s Plasco Building. Ghalibaf, who was in Qom at the time of the fire, was criticized by Iranians for not being in Tehran. Ghalibaf was also sullied by allegations of corruption concerning a donation by Tehran Municipality of 600 billion rials to a charity run by Ghalibaf’s wife. After he stepped down from the office of the mayor, members of the Tehran City Council accused Ghalibaf of billions of dollars in corruption. Despite these blemishes in his record, the supreme leader managed to find a landing spot for Ghalibaf, appointing him to the Expediency Council.

Seeking to capitalize on his management record, Ghalibaf embarked on additional runs for the presidency in 2013 and 2017. In 2013, with Rouhani winning 50.7 percent of the votes, Ghalibaf came in second place with only 16.6 percent. Four years later, he ran against Rouhani again but withdrew from the race and endorsed Rouhani’s conservative challenger Ebrahim Raisi. In the 2020 parliamentary elections, Ghalibaf won big—capitalizing on low voter turnout and his reputation in Tehran by winning the most votes there. In a sign of how the electoral landscape had shifted, the most votes in Tehran went to reformist Mohammad Reza Aref in 2016.

But as Ghalibaf makes a bid for the speakership, he is running into roadblocks—particularly concerns over his ambition, independent streak, and cases of corruption. Some factions view his bid with suspicion given rumors Ghalibaf wants to use the speakership as a means to run for the presidency in 2021. Also, because of his previous election campaigns facing off against Rouhani, Ghalibaf would preside over a more combative parliament. During his 2017 race for president, he railed against Rouhani for failing to create four million jobs and over “bad management.” Rouhani, in turn, accused Ghalibaf of wanting to “beat up students” after Ghalibaf boasted of doing so during the 1999 student demonstrations. Whether his brand of technocratic competence coupled with IRGC credentials overrides those concerns will be an early test of the new parliament’s priorities.

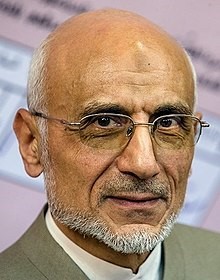

Mostafa Mirsalim: Mirsalim, an engineer by training, won the second most votes in Tehran after Ghalibaf in the 2020 parliamentary elections. A longtime fixture of Tehran’s political scene, Mirsalim served as chief of the national police in the early years of the regime. In 1980, he was considered by a parliamentary commission to become prime minister and was even nominated at one point by then-President Abolhassan Bani-Sadr. But Mirsalim lost out to Mohammad-Ali Rajai. In the years after, when Ali Khamenei won the presidency in 1981, Mirsalim became his chief of staff. Khamenei quickly became a patron of Mirsalim, reportedly favoring him to replace his rival Mir Hossein Mousavi as prime minister in 1985. But Ayatollah Khomeini insisted Mousavi stay in his post. After Khamenei ascended to the supreme leadership, Mirsalim served in the Rafsanjani administration as an advisor to the president and rose to become minister of culture and Islamic guidance. Before he even took office, Mirsalim railed against the “intellectual destruction of the Islamic Republic.” His tenure became synonymous with the closure of reformist publications. As former Vice Minister of Culture Ahmad Bourghani said of Mirsalim, his years at the ministry were “when space for the press completely closed up” after Mohammad Khatami attempted reform during his time as culture minister.

After Khatami won the presidential election in 1997, he quickly replaced Mirsalim, who then served for years as a member of parliament and a Khamenei appointee on the Expediency Council. In 2017, Mirsalim launched his candidacy for Iran’s presidency, facing off against Hassan Rouhani, who was running for reelection. During the campaign, officials in his camp focused on Mirsalim’s ethics, with one campaign aide saying, “Mr. Mirsalim talks according to law and the realities of the country. If he does not make the top goal scorer in the election, he is sure to win the title for the most ethical man.” In the debates, Iranian media noted that Mirsalim “didn’t receive much attention” and that he focused on the Rouhani government’s economic mismanagement. To distinguish his candidacy from the other conservatives running, he, unlike Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and Ebrahim Raisi, refrained from pledging to triple cash subsidies to the poor, dubbing them a “populist gambit.” Mirsalim stuck closely to the economic philosophy of Iran’s supreme leader, focusing on increased production, self-sufficiency, and the formation of a resistance economy. On the Iran nuclear deal, he said, “I am not against the JCPOA” but that the deal was based on “ambiguous text” and that others have not upheld their responsibilities under the accord.

Mirsalim represents a safe bet for traditional conservatives. His experience as Khamenei’s chief of staff, as a cabinet minister, member of the Expediency Council, and a longtime legislator also provide him with access and standing at the highest levels of the regime. Mirsalim is already playing a leading role in the early days of the new parliament, having been named interim deputy speaker until a permanent presiding board is selected. Such a role may also provide more visibility for his candidacy. But, his age—at 72—would make him the oldest individual ever to hold the speakership in the history of the Islamic Republic. That’s not to mention Mirsalim running against more colorful candidates like Ghalibaf who is known as an “authoritarian modernizer.” Mirsalim could also face questions surrounding a recent interview he gave to BBC Persian—an outlet the regime views with suspicion—previewing the new parliament.

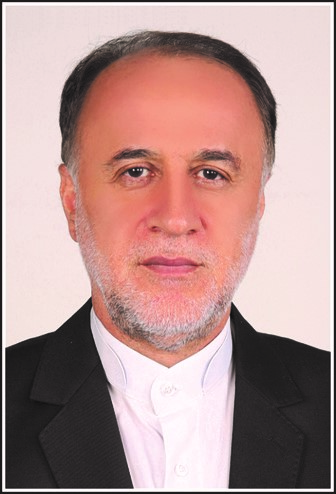

Hamidreza Hajibabaei: Hajibabaei is a veteran conservative legislator, serving four terms in parliament before Mahmoud Ahmadinejad promoted him to education minister during the second term of his presidency. Afterward, he returned to parliament. In a 2007 interview, he complained that the United States and Iran have not been able to forge a productive relationship because “over the past 28 years the various U.S. administrations have not allowed the Iranian and American nations to forge a friendship. They have always tried to keep the Islamic Republic of Iran [under a cloud] of accusations and to interpret our foreign policy for the American people in such different and unclear ways.” Hajibabaei also suggested Washington and Tehran might try a trial friendship for one year. Nevertheless, he employed standard regime messaging, listing grievances and calling for Iran to have a “powerful deterring position.”

In that same interview, which was conducted before his service in Ahmadinejad’s cabinet, Hajibabaei distanced himself from the then president’s style saying “I don’t want to say that I agree with everything Dr. Ahmadinejad says, with every word he utters, but his politics have been successful against the bullying and power plays of the United States.” As a member of parliament, Hajibabaei also traveled on a delegation to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where he expressed Iran’s desire to build relations with DRC based on Islamic values in contrast to “western countries and a number of big powers [who] strive to plunder the resources of the African nations and colonize them.”

When Hajibabaei took the helm of the Education Ministry, he said schools had a duty to “bring children’s hearts closer to God.” Hajibabaei spearheaded a plan, entitled “The Program for Fundamental Evolution in Education and Training,” which viewed schools as “neighborhood cultural bases,” and attempted to install clerics and members of the Basij alongside teachers to enforce such strictures. After Ahmadinejad’s presidency ended, Hajibabaei returned to parliament, where he continued to raise his profile, unsuccessfully challenging Ali Larijani for the speakership in 2018. He has also come out in favor of reducing ties with the United Kingdom after the British ambassador to Tehran was arrested in 2020.

Hajibabaei has the right mix of executive and legislative experience in his resume. Most speakers of parliament since 1979 have served in both executive and legislative positions. Hajibabaei’s extensive experience in parliament will serve him well in the upcoming contest, given the relationships he has cultivated through the years. Some analysts speculate he is the most well-positioned to take on Ghalibaf. There is precedent for veteran members of parliament to rise to the speakership—Mehdi Karroubi assumed the post after years in parliament. Hajibabaei’s cabinet experience also provides him with the management skills necessary for the job. But he was disqualified by the Guardian Council when he made a bid for the presidency in 2017, which may raise questions during his speakership candidacy.

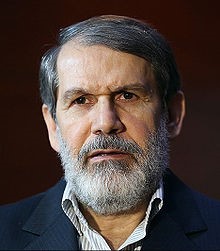

Morteza Aghatehrani: Aghatehrani is secretary-general of the Paydari Front, which is allied with the hardline Ayatollah Mohammad-Taghi Mesbah-Yazdi. Educated in Canada and the United States, he previously served as the head of the Islamic Institute of New York. Later, Aghatehrani went on to serve as an ethics teacher in Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s administration. During his tenure, Aghatehrani appeared close to Ahmadinejad. In 2011, amid a standoff between Ahmadinejad and Iran’s supreme leader over the fate of Intelligence Minister Heydar Moslehi, Aghatehrani was caught on video recounting a meeting with the president, in which Ahmadinejad told him “[Khamenei] gave me a deadline to make up my mind. I would either accept [the reinstatement] or resign.”

Aghatehrani also served as a member of the eighth and ninth parliaments. There, he focused on cultural issues as the head of parliament’s cultural commission. He led the charge against a permit granted for the screening of an Iranian movie, The Paternal House, saying “[i]t’s not right to attack our nation’s history with misguided ideas and [accuse] our forefathers of discrimination and violence against women.” On the leaders of the Green Movement, he said, “[i]n the case of a verdict of execution, they are ready to give a written oath to not tear the country apart, then we won’t object.” During his time in the legislature, reports circulated about Aghatehrani holding a U.S. green card, prompting him to retort “[t]hose people who speak about my green card should be asked whether they have seen my invalid [U.S. residency permit]? Do they even know what I was doing in the U.S.?”

Overall, Aghatehrani lacks the management experience of Ghalibaf, Mirsalim, and Hajibabaei. In fact, he would be one of the least qualified members of parliament to assume the speakership—Rafsanjani was an interior minister and Ali Larijani served as a cabinet minister and secretary of the SNSC before assuming the role, which compensated for the fact that they lacked extensive legislative experience. Aghatehrani shares none of those attributes.

Fereydoun Abbasi-Davani: Abbasi-Davani is new to electoral politics in Iran. A physicist and laser specialist by training, he worked as a professor at Shahid Beheshti University, where he focused on nuclear isotope separation and nuclear weaponization efforts. Over the years, Iranian media accounts have described him as a member of the IRGC and also a lecturer at the Imam Hossein University. Abbasi-Davani’s expertise was so dangerous that the U.N. Security Council instituted a travel ban against him. In 2010, men on motorcycles placed bombs on Abbasi-Davani’s car window, and seriously wounded him and his wife. Iran later blamed Israel for the attempted assassination. After this attack, Abbasi-Davani rose even further, with Iranian leadership installing him as head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI). One Western diplomat described him as “not as skillful—or as comfortable” as his predecessor, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)-trained Ali Akbar Salehi, who went on to become foreign minister. The differences did not end there. As United Against Nuclear Iran’s Advisory Board Member Ray Takeyh has noted, “Abbasi believed that Iran must continuously expand its nuclear capacity, even if it meant relying on primitive technologies.” This is in contrast to Salehi, who focused on more advanced centrifuges. Abbasi-Davani was also a champion of Iran’s enrichment of uranium to 20 percent, telling reporters in 2012 that Iran “will not suspend 20 percent uranium enrichment because of the demands of others.” That same year, the U.S. government sanctioned Abbasi-Davani.

After the election of Hassan Rouhani to the presidency, Salehi replaced Abbasi-Davani as head of AEOI for a second tour. Abbasi-Davani went on to win a seat in parliament and is now a contender to become speaker. Abbasi-Davani’s candidacy has symbolic value for the regime—someone steeped in Iran’s nuclear program who also survived an assassination attempt. He also has management experience having previously been at the helm of AEOI, and may be seen as a check on Rouhani, who could seek to revive the Iran nuclear deal after November. Abbasi-Davani has, at times, been a critic of the agreement, alleging that it permits International Atomic Energy Agency inspections of universities. However, his lack of experience in the legislature and Iran’s electoral system will be stumbling blocks in his candidacy.

Sadegh Mahsouli: An alumnus of the IRGC, Mahsouli went on to serve as a provincial governor, interior minister, and welfare and social security minister during the Ahmadinejad presidency. Mahsouli was interior minister during the crackdown on protesters, following Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s disputed reelection as president in 2009. The U.S. government included him on a list of persons who are complicit in human rights abuses in Iran. The U.S. Treasury Department found that “[h]is forces were responsible for attacks on the dormitories of Tehran University on June 15, 2009, during which students were severely beaten and detained. Detained students were tortured and ill-treated in the basement of the Interior Ministry building; other protesters were severely abused at the Kahrizak Detention Center, which was operated by police under Mahsouli’s control.”

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called Mahsouli a “billionaire general” who “went from being a poor IRGC officer at the end of the Iran-Iraq War to being worth billions of dollars. How’d that happen? He somehow had a knack for winning lucrative construction and oil trading contracts from businesses associated with the IRGC. Being an old college buddy of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad just might have had something to do with it as well.”

Mahsouli will likely play a decisive role in Ghalibaf’s ability to become speaker, as there are some reports Mahsouli is not himself a candidate for the speakership but is building a coalition against him. Mahsouli has critics, as evidenced by Ahmadinejad’s withdrawal of his nomination as oil minister after questions were raised about the sources of his wealth. Nevertheless, given his wealth and management experience, his role in this process will be important to monitor

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.