Mojtaba Khamenei: The Supreme Leader’s Gatekeeper & Guardian

Download PDFPage Navigation

Mojtaba Khamenei has emerged as an enigmatic but powerful figure in the Iranian system. Mojtaba is the second-eldest son of Ali Khamenei. His power stems not only from his family connection but also from the role he plays in the Office of the Supreme Leader. Mojtaba occupies a similar role to that of Ahmad Khomeini during Ruhollah Khomeini’s supreme leadership—a combination of aide-de-camp, confidant, gatekeeper, and power broker. Mojtaba has become so influential in the Iranian establishment, that some analysts consider him to be a contender to succeed his father as supreme leader.

Mojtaba’s Khamenei’s Early Years

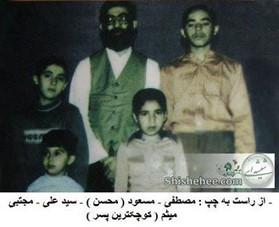

Undated photo of Ali Khamenei and his sons Mostafa, Masoud, Mojtaba, and Meysam Khamenei

Undated photo of Ali Khamenei and his sons Mostafa, Masoud, Mojtaba, and Meysam Khamenei

Born in Mashhad in 1969, Mojtaba Khamenei’s early childhood coincided with his father emerging as a leading revolutionary against the Iranian monarchy of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. During these years, Ali Khamenei, the future supreme leader, led religious classes in three mosques in Mashhad. According to his official biography, Khamenei became so threatening to the Pahlavi monarchy that the National Security and Intelligence Organization (SAVAK) raided his home in Mashhad in the winter of 1975 and arrested him for a sixth time. Even though Khamenei was later freed, SAVAK detained him again in the winter of 1976 and sentenced him to exile for three years. In one retelling on Khamenei’s website, his eldest son, Mostafa, watched his father being beaten during an arrest, and when the SAVAK agents wanted to tell Khamenei’s sons he was going on vacation, the future supreme leader insisted Mojtaba and the others, who were sleeping, be told the truth. Thus Mojtaba’s early years were colored by these experiences.

Photo of the Habib Battalion during the Iran-Iraq War (Photo via Radio Farda)

Photo of the Habib Battalion during the Iran-Iraq War (Photo via Radio Farda)

Following the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the family’s political fortunes changed dramatically. Khamenei went from being an outlaw to serving in key posts like deputy defense minister. This resulted in a move from Mashhad to Tehran—where Mojtaba attended Alavi High School, a training ground for regime elites. Other graduates of Alavi High School include former Foreign Ministers Ali Akbar Velayati and Javad Zarif as well as former Speaker of Parliament Gholam Ali Haddad-Adel. There, Mojtaba received both a general and religious education, graduating in 1987.

Mojtaba also served in the armed forces during the Iran-Iraq War, specifically the Habib Battalion. The Habib Battalion enabled Mojtaba to forge relationships with men who would move on to become leading members of the Iranian security services, including Hossein Taeb, the future head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) Intelligence Organization as well as Hossein Nejat, who is the commander of the IRGC’s Sarallah Headquarters, which manages security in Tehran. Nejat had also served as deputy to Taeb at the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization. These figures’ promotion through the ranks is indicative of their closeness to the Khamenei family, and particularly Mojtaba. There is evidence that Mojtaba, along with the sons of other officials, went missing at one point during his service in the Iran-Iraq War during the recapture of Mehran. But they later reemerged.

The Elevation of Ali Khamenei as Supreme Leader

In 1989, Mojtaba’s life changed when Ali Khamenei was elevated as supreme leader after Khomeini’s death. He went from the son of the deputy defense minister turned president to being the son of the supreme leader. During these early years of Khamenei’s supreme leadership, Mojtaba launched his clerical studies—learning in Tehran from his father and Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, who would later become chief justice. Later, in 1999, he would move to Qom, where he was educated by the influential and archconservative cleric Ayatollah Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah Yazdi, Ayatollah Lotfollah Safi Golpayegani, and Ayatollah Sayyed Mohsen Kharrazi. That the clerical elite flocked to Mojtaba was a sign of his status as one of the supreme leader’s favored sons. Mesbah-Yazdi was known for his radical views—once writing that Iran had the right to acquire “special weapons”—widely interpreted to mean nuclear weapons. In 1998, he charged that “Democracy means if the people want something that is against God’s will, then they should forget about God and religion. Be careful not to be deceived. Accepting Islam is not compatible with democracy.” That Mojtaba learned from Mesbah-Yazdi, whose views—and disdain for—the republican aspects of the Iranian system is noteworthy given speculation that surrounds Mojtaba’s own stock as a potential candidate to succeed his father as supreme leader. If this elevation takes place, it would position the supreme leadership as akin to a hereditary monarchy. Nevertheless, despite his clerical education, leaked diplomatic cables suggested Mojtaba “is reportedly not expected to achieve by his own scholarship the status of “mujtahid.” He is not even an ayatollah at this juncture. Although some accounts depict him as teaching at a senior level in Qom.

In the late 1990s, Mojtaba’s profile began to rise. As noted by Iran Wire, the memoirs of former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani include an entry that Mojtaba had requested an assessment from the editor of Resalat about the situation in Iran’s universities in January 1998. The timing of the entry is noteworthy as it happened at the dawn of the presidency of reformist Mohammad Khatami, whose tenure later witnessed a student uprising in July 1999. Even in these early years of Khamenei’s supreme leadership—less than ten years into his term—Mojtaba was a fixture at his father’s side.

Beginning in 2005, reports emerged of Mojtaba playing a leading role as a power broker in presidential elections. Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of the Iranian parliament and then a candidate for president, alleged that Mojtaba provided crucial backing to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005 after initially backing Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, resulting in Ahmadinejad’s rise. Leaked diplomatic cables, citing accounts from dissidents, suggested initially that “Mojtaba was reportedly the “backbone” of Ghalibaf’s past and continuing election campaigns. Mojtaba is said to help Ghalibaf as an advisor, financier, and provider of senior-level political support.” Mojtaba’s meddling did not go down well with different actors in the Iranian system—sparking protests by Karroubi and others.

In the 2009 election, these interventions continued, with reporting that Mojtaba engineered Ahmadinejad’s presidential reelection victory and even instructed the Basij to aggressively clamp down on Green Movement demonstrators. Mojtaba was depicted as working closely with allies like Hossein Taeb, a fellow member of the Habib Battalion, to crush dissent from the Office of the Supreme Leader.

While in his father’s office, there is also evidence to suggest Mojtaba commanding considerable Iranian financial resources. In 2009, the UK government froze a bank account worth around $1.6 billion, which was rumored to be under the control of the supreme leader’s son himself. Mojtaba was later sanctioned by the United States under Executive Order 13867 in 2019 for “representing the supreme leader in an official capacity despite never being elected or appointed to a government position aside from work in the office of his father.” Importantly, the US Treasury Department revealed that the supreme leader “has delegated a part of his leadership responsibilities” to Mojtaba and that he works closely with the commander of the IRGC’s Quds Force and the Basij Resistance Force—giving him domestic and international security credentials.

Mojtaba has also been active in the oversight of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) organization. In 2014, reports emerged that the then director of IRIB Mohammad Sarafraz was fired from IRIB amid pressure from Mojtaba and the IRGC—particularly in collaboration with Hossein Taeb. In this episode, the handiwork of the Habib Battalion network once again can be seen.

This shows that Mojtaba is a close associate of his father—with leaked diplomatic cables claiming that he has been “second only” to the head of the Office of the Supreme Leader Mohammad Mohammadi Golpayegani. There is a precedent to this arrangement in the role that Ahmad Khomeini played for his own father between 1979-89. During Ahmad’s time as gatekeeper for the supreme leadership, speculation emerged that he too was a prime contender for the supreme leadership, as Mojtaba is today. The parallels to Ahmad and Mojtaba are significant—both had inferior religious ranking punching above their weight and using their father’s offices as a platform to expand their power base. Like Ahmad chastising Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, once the designated successor to his father, in a leaked and lengthy memorandum, Mojtaba has meddled in positioning dependable allies and sidelining untrustworthy adversaries in the Iranian system.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s four sons: (L to R): Mostafa, Masoud, Mojtaba, and Meysam

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s four sons: (L to R): Mostafa, Masoud, Mojtaba, and Meysam

But Ahmad’s experience is also a warning for Mojtaba. Despite all the speculation he was a prime contender for the leadership, Ahmad Khomeini was sidelined and Ali Khamenei was elevated to the post in 1989. Khomeini and his family were eventually marginalized from the Iranian power structure. He merely served as Khamenei’s own representative on the newly-formed Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) beginning in 1989 and was the overseer of his father’s mausoleum—nothing more. Then, in 1995, Ahmad died suddenly from cardiac arrest, at the young age of around 50—a death that some have deemed suspicious. Mojtaba is likely well aware of this precedent, and thus has been building the requisite protection within the system for any eventuality—whether supreme leadership or no supreme leadership.

Mojtaba, who is married to the daughter of former Speaker of Parliament Gholam Ali Haddad-Adel, is the most powerful of Iran’s supreme leader’s sons. Although his other sons are active in the Office of the Supreme Leader. Masoud Khamenei, who is married to the niece of former Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi, is reportedly active in the Office of Preserving and Promoting the Works of the Leader of the Islamic Revolution. Mostafa Khamenei, married to the daughter of Ayatollah Aziz Khoshvaght, devotes most of his time to religious studies. Meysam Khamenei, married to the daughter of a prosperous Tehran bazaar merchant Mahmoud Lolachiyan, has been described in some accounts as being politically active, but less influential than Mojtaba.

Mojtaba Khamenei’s Future Prospects

The ascension of Ebrahim Raisi as president in 2021 has led many observers to view him as a natural successor to Iran’s supreme leader. This is because of Raisi’s position in the Iranian system as a cleric who will have had experience presiding over two branches of the Iranian state—the judiciary and the presidency. Raisi is arguably the most qualified individual—in terms of resume—to succeed Iran’s supreme leader. However, traditionally Iran’s presidency is the office that absorbs most of the accountability and blame in Tehran. The experience of his predecessors—particularly Hassan Rouhani whom some observers at one point viewed as a leading contender for the supreme leadership himself—is instructive. They left the presidency degraded and diminished.

Thus if Raisi shares a similar fate, Mojtaba’s stock could rise as a potential successor to his father. This is especially the case if Iran’s supreme leader expresses a wish for his son to succeed him. This is also where Mojtaba’s close ties with the IRGC could make a difference—he has helped install allies and influence in the extraterritorial Quds Force, the Intelligence Organization, as well as influence over the Sarallah Base. There is evidence that some parts of the Iranian establishment seek to inflate Mojtaba’s religious credentials—some, albeit few, media reports even refer to him as an ayatollah, a rank he does not have. Separately, unofficial posters have been found in Tehran in recent years promoting Mojtaba’s supreme leadership candidacy. Other contenders for the supreme leadership have also been subject to media campaigns to inflate their religious credentials—Raisi himself held the rank of hojatoleslam but soon after he became chief justice and then later president, he was gradually referred to as an ayatollah.

But that does not mean Mojtaba would not face obstacles. Some accounts suggest despite Mojtaba starting senior-level jurisprudence classes in Qom, certain clerics scoffed at Mojtaba taking such seminars because of suspicions he would use them as a platform to further his succession credentials. Such pushback may resurface should Mojtaba be seriously considered by the Assembly of Experts for the supreme leadership.

Another important aspect to succession is the role that Mojtaba would play should his father become incapacitated. While he would not be constitutionally empowered to serve on an interim leadership council, Mojtaba could play a significant role in such a situation. But the road ahead for Mojtaba is not without risks, especially considering the experience of Ahmad Khomeini, another ambitious son to a supreme leader, who eventually lost his position and his life.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox

The Iran nuclear deal is done. And the world's biggest companies have already visited Tehran ready to strike a deal when sanctions end. These businesses will add even more to Iran's bottom line. And that means continued development of nuclear technologies and more cash for Hamas and Hezbollah.