As the Khomeinists maneuvered to increasingly encroach upon all facets of state administration and consolidate power, Ali Khamenei’s fervent loyalty to Khomeini and close relationship with Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who was Khomeini’s closest acolyte, began paying dividends. Throughout the 1980s, an extremely bloody decade during which Iran’s revolutionary regime simultaneously faced intensifying domestic strife and a protracted war with neighboring Iraq, Khamenei rose through the ranks and was appointed to several important posts by Khomeini, boosting his public profile and revolutionary bona fides. Still, there was very little indication during the years between the revolution and Khomeini’s death that Khamenei would eventually outmaneuver his allies and rivals to become the Islamic Republic’s most important official.

Khamenei’s first role after the revolution was serving as one of the founders of the Islamic Republican Party. According to his official biography, Khamenei was among those who crafted the platform and manifesto for the party and was the founder of the party’s central committee. He actively communicated the party’s message through speeches and pamphlets and founded a newsletter that served as the party’s mouthpiece.

Soon after the revolution, Khamenei, who had previously been a somewhat atypical cleric involved in intellectual and literary pursuits, began taking an interest and playing an active role in military affairs. His role in security would influence his approach to consolidating power as Supreme Leader, which relied heavily on creating patronage links at all levels of Iran’s military, security, and intelligence apparatuses.

Asserting clerical control over the Islamic Republic’s military and security agencies, which retained vestiges of loyalty to the Shah’s regime, was an ongoing challenge for Khomeini and his followers in the aftermath of the revolution. Accordingly, the Khomeinists applied a two-pronged approach, purging the military from the top down of officers and conscripts with ties to the Shah or who were deemed disloyal to the Islamic Revolution, and simultaneously, reorganizing the military’s command and control structures to ensure clerical oversight over defense policy and planning. The overarching goal of the Khomeinists was to ensure that all facets of state security were in ideological lockstep with the goals and values of the Islamic Revolution.

As the Islamic Revolutionary Council and Islamic Republican Party maneuvered to compete with Bazargan’s provisional government by placing Khomeinists in strategic positions, Khamenei was appointed Deputy for Revolutionary Affairs in the Defense Ministry in late July 1979. Little has been written about his tenure, but based on his title, he was likely engaged in efforts to purge counterrevolutionary elements and sentiment and instill ideological conformity with the aims of the Islamic Revolution in the armed forces. He held the position until the fall of the provisional government on November 6, 1979, just days after the occupation of the U.S. Embassy by radical student followers of Khomeini.

When the siege of the U.S. Embassy occurred, Khamenei was in Mecca experiencing the hajj with Rafsanjani. Rafsanjani’s account of hearing the news shows that neither he nor Khamenei initially supported the embassy takeover. Rafsanjani recounted, “We were surprised because we did not expect such an incident. It was not our policy…It was obvious that neither the Revolutionary Council nor the interim government had any inclination toward such acts.” If Khamenei did have misgivings about the embassy seizure, he chose never to air them publicly, as such a break with Khomeini would have imperiled his political future.

In Khamenei’s recounting, he backed the takeover from the outset as soon as it was clear that the hostage takers were Khomeinists. According to Khamenei, the more liberal members of the Islamic Revolutionary Council feared that America would respond to the hostage crisis in a manner that would topple the revolution. Khamenei consistently defended the actions of the students in deliberations with the Council and gave a speech outside the Embassy compound during the holy month of Muharram in which he noted, “Not only we did not lose anything in this campaign against America, but we gained something, which was giving hope to the people and glorifying the revolution. This helped us elevate the image of Iranians in the world.” Khamenei believed that revolutionary regimes historically suffered from retaining relationships with their former colonial masters. He approved of the embassy takeover, because it severed linkages between Iran and the U.S. After he was chosen as the representative of the Revolutionary Council, Khamenei would defend Iran’s treatment of the hostages and accompany foreign reporters who were permitted to interview the Americans.

In December 1979, Khamenei was appointed as supervisor of the IRGC, a position he held three months before resigning to run in the first majles election. In January 1980, Ayatollah Khomeini issued a decree appointing Khamenei as the Friday prayer leader for Tehran, a position which greatly enhanced his public profile. Friday prayer leaders in cities around Iran were an important force multiplier for Khomeini’s efforts to convey his ideology and strategic positions to his followers as he consolidated power. Giving Khamenei the most prominent Friday prayer leadership showed Khomeini's high regard for his communication skills. According to his official biography, Khamenei came up with the innovation of holding congresses of Friday prayer leaders to ensure that Khomeinist clerics within Iran – and eventually, at Khomeinist institutions outside of Iran’s borders – delivered unified messages each week. A New York Times profile wrote of Khamenei’s tenure as Friday prayer leader, “For more than a year, the slim, intense clergyman delivered fiery sermons before large crowds. He usually spoke with a rifle in his hand, jabbing its muzzle into the air to make his points as he castigated the “Great Satan, America,” the leaders of Iraq and the political foes of Ayatollah Khomeini.”

Following the passage of Iran’s constitutional referendum in December 1979, the country turned its attention to its first-ever presidential and majles elections in early 1980. Khomeini was wary of the potential backlash among secular and moderate Iranians if the proceedings gave off the appearance of an imposition of clerical rule over Iran’s nascent republican institutions. In the interest of legitimizing the Islamic Republic’s new hybrid system among the population writ large, not just his followers, Khomeini barred clerics from running for the presidency. Numerous other candidates were also disqualified, including Mas’ud Rajavi, the leader of the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK). This Islamist Marxist movement was part of the coalition to oust the Shah. However, Khomeini sidelined it after the revolution due to its rejection of velayat-e faqih and the decision to boycott the December 1979 referendum.

The IRP’s lay candidate had to withdraw when it came out that his father was Afghan, contradicting the new Constitution’s demand that the President be of Iranian origin and nationality. He was replaced by an obscure candidate who came in a distant third, garnering just over 3 percent of the vote. Despite the IRP’s paltry showing, the election did not indicate that the Khomeinists lacked favor with the population, nor was it a sign of organizational weakness. The winning candidate, Abolhassan Banisadr, who amassed more than 75 percent of the vote, was popular with the left but was also closely associated with Khomeini in the public’s mind due to his role as an advisor during Khomeini’s exile in Paris. Banisadr favored an Islamic government for Iran, although his vision was more democratic than Khomeini’s. He saw Khomeini in the pre-revolutionary period as a useful vessel to gin up anti-Shah and anti-foreign domination sentiment. He helped make Khomeini a palatable figure among Iran’s intelligentsia. Thus, Khomeini saw Banisadr as a figure he could work with until he was no longer useful.

Banisadr was inaugurated as a powerful figure on February 4, 1980, serving as President and head of the armed forces and Supreme Defense Council after Ayatollah Khomeini transferred his constitutional authority as commander-in-chief to Banisadr. Reflecting Khomeini’s support, Khamenei, in his capacity as Tehran Friday prayer leader, exhorted his followers to “respect him, follow him, support him in the field, cooperate with him, do not undermine him.” The goodwill would not last, however, as Banisadr saw in his victory a mandate to chart a more moderate course for the revolution and to rein in clerical power. In his words, he sought to rescue the revolution from “a fistful of fascist clerics.” He abortively sought to pursue an agenda that included integrating the IRGC into the regular army, dissolving revolutionary courts and reestablishing a centralized justice system, and doing away with the excesses of property expropriation to create a stable economic development and investment environment.

The IRP, led by its powerful secretary-general, Ayatollah Beheshti, offered Banisadr limited support at the beginning of his presidency, conditioned on following the Khomeinists’ preferred path of militant Islamism. Ayatollah Khomeini also appointed Beheshti as chief justice of the supreme court, and his control over the IRP and judiciary gave him considerable influence over the Khomeinists’ primary instruments of revolutionary terror. Beheshti’s appointment as chief justice further ensured that Iran’s legal system would be immune to secularist or liberal reformation efforts and instead take an Islamist trajectory. Banisadr’s agenda, which called for a “year of order and security,” was essentially predicated on reining the Khomeinists’ excesses. So he was frustrated at every turn by the IRP, which was loath to integrate its parallel network of institutions, such as the IRGC and revolutionary tribunals, into a unified central government.

The limitations on Banisadr’s power became apparent early on due to the growing ascendance of the IRP, which won an outright majority of seats in the majles elections held in March 1980. Unlike the presidential election, Khomeini explicitly encouraged clerics to run for the majles and called on the population to “vote for only good Muslims.” In addition to placing his thumb on the scales in this manner, Khomeinist thugs in the komitehs attacked rallies and offices of rival parties, most notably the Mojahedin-e Khalq, which failed to win a single seat despite its growing popularity.

Following its resounding victory in an election marred by allegations of intimidation and irregularities at the polls, the Khomeinist majority selected Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani as Speaker of the Parliament. Ali Khamenei had resigned as head of the IRGC to run in the majles elections, and he won a seat as a representative from Tehran. Reflecting his good standing with the party, Khamenei served as the head of the defense committee, where he prioritized bolstering the IRGC’s armed strength and integrating the Basij, irregular paramilitary volunteer units, into the IRGC.

Over the next few months, bitter wrangling ensued as the IRP moved to block several of Banisadr’s allies from serving in his cabinet, as well as his preferred choices for prime minister, leaving him no choice but to select an IRP candidate, Mohammad Ali Rajai. Banisadr had hoped that his ability to handpick a prime minister would enable him to appoint an ally who would be a rubber stamp for his agenda, ensuring that the presidency would evolve as a stronger office than the prime minister. He failed to predict the IRP’s dominance at the polls, which stripped him of that ability. As a result, the prime minister became a more powerful position until the role was eventually abolished. Banisadr frequently clashed with Rajai, whom he viewed as an incompetent ideologue. However, Rajai had the upper hand due to the backing of Beheshti and the IRP, although Khomeini himself tried to stay above the political fray.

Months into his presidency, the IRP controlled the parliament, the judiciary, and the president’s cabinet, ensuring that Banisadr could not govern effectively. The ascendant IRP moved to purge modernists and technocrats from government ministries, replacing them with revolutionaries acceptable to the emerging Khomeinist order. The Islamic Revolutionary Council formally launched a cultural revolution during this period, which also sought to transform Iran into a conservative Islamic society through repression, purging any vestiges of Western, liberal culture and values. Iran’s universities were the primary battleground, as they were the focal point for leftist and liberal education and political organizing.

Ayatollah Khomeini set the stage for an attack on Iran’s universities in April 1980, declaring, “We are not afraid of economic sanctions or military intervention. What we are afraid of is Western universities and the training our youth in the interests of West or East.” Shortly after that, Khomeinist komitehs violently clashed with leftists, forcing them out of universities. Professors, many of whom had actively opposed the Shah, were now deemed insufficiently revolutionary and were dismissed. Ultimately, Iran’s universities were shut down for three years while the newly formed High Council on the Cultural Revolution moved to Islamize the curriculum of Iran’s entire education system.

The Khomeinists also moved to pressure women from participation in public life and imposed repressive mores against them. The number of political prisoners ballooned during this period to pre-revolutionary levels, and executions of political prisoners and those accused of morality crimes increased. Many professors, students, doctors, and engineers fled Iran, creating a dearth of expertise that has plagued the country today. The Iranian system was effectively recalibrated to prioritize devotion to Islam and the revolution over technocratic expertise.

In September 1980, the Iran-Iraq War threatened to topple Iran’s post-revolutionary government but instead actually accelerated the Khomeinists’ consolidation of power. Saddam Hussein, the Sunni leader of a majority Shi’a nation, was wary of the Islamic Revolution next door, which had energized Iraq’s oppressed Shi’a population, and of the Khomeinists’ explicit desire to export the revolution. Khomeini hated Hussein ever since being banished from Najaf and frequently demonized the secularist leader publicly as an infidel. Unsatisfied with a 1975 treaty inked with the Shah to resolve a border dispute over the Shatt al-Arab River, Hussein saw an opportunity to redraw the map in his favor and blunt the momentum of the Islamic Revolution in its infancy.

Sensing the Islamic Revolutionary regime was weak and vulnerable due to the domestic political turmoil and ethnic unrest gripping the country and its international isolation as a result of the still-ongoing hostage crisis, Hussein launched a surprise invasion on September 22, 1980, seeking to seize the oil-rich province of Khuzestan, which also contained numerous strategic waterways and coastal access to the Persian Gulf. The Iranian armed forces were in disarray on the eve of the Iran-Iraq War due to ongoing purges of its officer class and the inability to procure needed weaponry and parts from the West. Iran’s defenses along the Iraqi border were weak, as much of the military’s existing capacity was tied up in pacifying ethnic conflicts in restive provinces.

Hussein thought the Arab population of Khuzestan, which had been agitating for local administrative and cultural autonomy, would welcome his incursion and rise on behalf of Iraq. However, instead, the war united Iranians under the banner of nationalism. The Khomeinists sought to imbue the fighting with Shi’a symbolism and appeals to martyrdom, which inspired huge numbers, particularly of the basij, to give their lives in “human wave” assaults to repel the Iraqi invasion. Iranians of all backgrounds rallied to the flag and joined in the cause of the “Sacred Defense” of their homeland. The Iran-Iraq War further hardened enmity toward the U.S. as well, as Khomeini and his followers viewed the conflict as an imposed war on behalf of American and Western interests to topple the Islamic Revolution and gain back control over Iranian energy resources and strategic waterways. The U.S. did not encourage Saddam Hussein to invade Iran, nor did it actively arm him until Iran had gained the upper hand in the conflict. In their conspiratorial worldview, the U.S. and its allies opposed a revolutionary, independent Iran that would not uphold their interests in the region and would go to great lengths to sabotage the revolutionary regime and return Iran to a vassal state. Saddam Hussein’s brutality in waging war, including using chemical weapons and carrying out aerial bombings of civilian population centers, had long-lasting psychological scars and are used to the present day as evidence of U.S. perfidy and to justify claims that the U.S. existentially threatens the Islamic Revolution.

Ali Khamenei was active in the war effort from the outset, participating in military planning meetings on responding to the Iraqi invasion. Days into the conflict, he volunteered to go to the front lines to prepare a report on the condition of Iranian forces and their needs. He would spend the first few months of the war, from September 1980 until June 1981, going back and forth between the front lines. He was not on active duty but did assist combatants and participate in some operations while continuing to perform his duties as Friday prayer leader. During this period, Khamenei also served as Khomeini’s representative on the Supreme Defense Council, an umbrella body created in October 1980 to serve as a unified command for Iran’s conventional armed forces and the IRGC. Khomeini appointed Banisadr as the chairman of the Supreme Defense Council. This position gave him the trappings of authority and made him a convenient scapegoat set up to fail.

Despite the efforts to align the activities of Iran’s conventional and irregular forces, tensions remained, and the Khomeinists’ mistrust of the conventional military continued unabated. These tensions would contribute to the undoing of President Banisadr, who backed the conventional armed forces over the IRGC. The Khomeinists suspected Banisadr would use his ties to the conventional forces to launch a coup. They leveraged these fears to secure better equipment for the IRGC, allowing it to strengthen its position relative to the conventional forces. According to a study of the Iran-Iraq war by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “The situation was made worse because the regular forces tended to husband their resources while trying to organize for counteroffensives, while the Pasdaran (IRGC) infantry was constantly at the front of the day-to-day fighting and took most of the casualties. The Pasdaran got virtually all the favorable coverage in the Iranian media, while the Mullahs began to accuse the regular forces of sacrificing the Pasdaran while protecting their own lives. The net result was that President Banisadr increasingly came to rely on his role as commander-in-chief of the regular forces as a basis for power under conditions which cost him both religious and popular support.” During this period, the IRGC expanded through recruitment, as it came to be mythologized as the true guarantor of the revolution. It also became a more sophisticated, professionalized, and better armed fighting force with invaluable combat experience.

Unmoved by the prevailing spirit of unity in the country, Banisadr and the IRP did little to temper their infighting during the early months of the conflict. Prime Minister Rajai sought to sideline Banisadr at every turn, prompting Banisadr to write a confidential letter to Khomeini in October 1980 appealing to him to dismiss Rajai and dismantle the IRP-dominated government, which he claimed was incompetent, lacked public support, and had declared war on his presidency. Using the war emergency as a pretext, the Khomeinists increased their repression within Iranian society, intensifying the ongoing Cultural Revolution and prosecuting the war on their opponents with the same vigor as the conflict against Iraq, shuttering newspapers and tamping down on dissent. The Khomeinist revolutionary komitehs, which Banisadr had sought to rein in, reasserted their presence, enforcing curfews and establishing patrols to monitor for “subversives.”

With his reform agenda frustrated, Banisadr sought to resolve his differences with the Rajai government. He also frequently began meeting with Ayatollah Khomeini to implore the Supreme Leader to mediate on his behalf. When this approach failed to yield progress, he went on the offensive against the IRP. Banisadr began traveling around the country, making speeches and holding rallies where he attacked his clerical rivals. He began writing a daily column in his newspaper where he openly aired his political grievances. In his columns, he compared the IRP’s dominance to the era of single-party rule under the Shah, labeled the Cultural Revolution as an attack on knowledge and expertise because the IRP had neither, and accused the Khomeinists of frequently engaging in torture, an emotionally fraught accusation given the torture many revolutionary leaders suffered under the Shah.

Banisadr’s incendiary attacks on the IRP were tantamount to sedition in the eyes of the Khomeinists. They responded by denigrating his loyalty to Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution and began using their informal power structures to censor and harass Banisadr and his allies. Club-wielding komitehs broke Banisadr’s speeches and rallies, and the IRGC and revolutionary courts escalated arrests and harsh punishments of opposition elements. According to scholar Shaul Bakhash’s historical account of the period, the Khomeinists “deliberately worked to sharpen the dispute into a struggle between Islam and secularism, the clerics and the Westernized intellectuals, revolutionary steadfastness and compromise, and ultimately, loyalty and disloyalty to the person of Khomeini.”

As the pressure campaign against Banisadr mounted, the MEK, an organization far to his left, increasingly allied with the beleaguered president. The MEK backed Banisadr’s calls for pluralism, free speech, and association, which they saw as necessary for their continued political survival. They saw in the moderate Banisadr a vehicle that could lead the radical group to more mainstream acceptance among the middle classes. The MEK mobilized its followers to attend Banisadr’s rallies, providing a force that could fight back against the komiteh’s attempts to violently break up these demonstrations. Still, the MEK’s opposition was fractious. Banisadr and his supporters among bazaari and conservative religious camps chafed against drawing too close to the MEK’s Marxist economics and calls for secularist governance.

While the MEK attempted to fight back against the komitehs, they were outmatched by the brutality of the club and switchblade-bearing Khomeinist partisans, which killed dozens of their opponents in street clashes around the country in the final months of Banisadr’s presidency. Banisadr continued to appeal to Khomeini to rein in this street justice. However, Khomeini and other IRP officials offered only feeble condemnations of hooliganism while blaming Banisadr for stoking the masses' anger. While Khomeini’s sympathies lied with his partisans, he did not fully break with Banisadr, as he still needed buy-in from Banisadr’s constituencies to keep the revolutionary regime afloat. As Banisadr drew closer to the MEK and increased his denunciations of Khomeini’s closest clerical allies and the excesses of the revolution, however, Khomeini’s support waned.

Khomeini made one final attempt to mediate the dispute between Banisadr and the IRP in March 1981. Khamenei was among the IRP leaders brought into the meeting, alongside heavyweights such as IRP Secretary General and Chief Justice Ayatollah Beheshti, Parliament Speaker Rafsanjani, and Prime Minister Rajai. After the meeting failed to yield progress, Khomeini reiterated his support for Banisadr as commander-in-chief and banned both sides from further speeches or articles that would contribute to factionalism. While ostensibly a neutral ruling, Khomeini took away Banisadr’s ability to press his case to the populace, forcing him to silently acquiesce to being a figurehead president with all the real power in IRP control. Convinced of his popularity, Banisadr soon resumed public denunciations of the IRP in his newspaper and at demonstrations, increasingly challenging Khomeini’s authority directly. After calling on his supporters to resist the revolutionary regime’s slide to dictatorship, tantamount to calling for an uprising, Khomeini finally withdrew his support for Banisadr. On June 7, 1981, his newspaper was banned; days later, Khomeini stripped him of his role as commander-in-chief.

Having finally lost Khomeini’s support and recognizing that the IRP was increasing its repression of opposition elements, Banisadr hid. Rafsanjani initiated impeachment proceedings against him in the majles on June 20 and 21, 1981. By this time, arrests and executions of his aides and violent crackdowns on his backers had begun in earnest. As the majles debated, hostile crowds outside chanted “Death to Banisadr,” vowing retribution against any legislators who defended him. Given the charged atmosphere, only a handful of the 40-45 members who supported Banisadr’s agenda dared speak in his favor. Banisadr was overwhelmingly impeached and removed from office, with only one member voting against the action and several more abstaining.

The elimination of Banisadr proved an insurmountable setback for the loose coalition of moderate and leftist forces in the country. In the run-up to his impeachment, the MEK and the National Front had organized what they hoped would be mass demonstrations of support for Banisadr and against the IRP. However, these failed to move the needle, especially as many sympathetic to their ideologies opted not to take to the streets over fears of Khomeinist club-wielding hooligans. On the actual day impeachment proceedings began, the MEK, backed by almost all other opposition groups, called for Iranians to march against dictatorship, which according to Baqer Moin, was “the most direct challenge to Khomeini since the revolution, and an unmistakable attempt to overthrow the religious establishment.” The IRGC joined forces with the Khomeinist komitehs to suppress the demonstrations, opening fire on the crowd in Tehran, arresting hundreds, and reportedly carrying out summary executions of MEK supporters on the spot.

Following his impeachment, Banisadr issued calls for a mass uprising from hiding. Khomeinist forces, meanwhile, continued suppressing ongoing, sporadic MEK-led demonstrations, leading the group to change tactics in favor of armed rebellion. Banisadr opted to fully embrace the MEK at this point and entered into a formal alliance with the group. A month later, Banisadr and the MEK’s leader, Masud Rajavi, fled Iran and settled in Paris, where Banisadr was an advisor to Ayatollah Khomeini before the Revolution. This time around, Banisadr and Rajavi would work to overthrow Khomeini, creating the National Council of Resistance, an umbrella group for Iran’s beleaguered opposition factions to coordinate their anti-regime activities and plans for governance if they succeeded in toppling the Islamic Revolution.

Banisadr’s impeachment touched off an era of guerilla warfare between liberal and leftist forces led by the MEK and the Khomeinists. The MEK’s strategy was first to destabilize the regime by assassinating key leadership, then crippling it through large-scale demonstrations and strikes that it hoped would lead to a mass uprising and regime overthrow. The MEK’s assassination campaign would eliminate many of the key figures within the IRP, some of whom presumably would have been ahead of Khamenei in the queue for the prime leadership roles he went on to obtain.

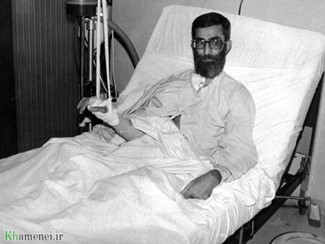

Ali Khamenei was the first figure targeted in the assassination campaign. On June 27, 1981, Khamenei returned to Tehran from one of his sojourns to the Iran-Iraq War battlefield as Khomeini’s representative on the Supreme Defense Council. While delivering a speech at the Abuzar Mosque in southern Tehran, a bomb placed in a tape recorder on the table before him detonated, gravely wounding Khamenei. In his telling, his pulse briefly stopped following the blast. Khamenei was hospitalized for 42 days and suffered hearing loss, lung and vocal cord damage, and permanently lost the use of his right arm. According to a relative who grew up with Khamenei, the bombing changed Khamenei and “made him deeply angry inside – it gave him a grudge against people.” It is unclear which faction was behind the bombing; it was initially attributed to the Forqan group, a militant Shi’a organization opposed to the existence of clergy. However, today, Khamenei and the regime allege that the MEK was behind the plot in their propaganda materials.

Khamenei’s miraculous survival enhanced his prestige in Khomeinist circles, and he came to be seen as a “living martyr.” Ayatollah Khomeini sent Khamenei a note filled with fulsome praise, showing the high esteem in which he held his protégé, in which he declared, “Today the enemies of Islam have carried out an assassination attempt on you, the one who is from the genealogy of the tribe of Imam Hossein, the son of ‘Ali. You have done nothing but serve Islam and this country. You have been a faithful soldier at the frontlines, and a passionate teacher for the public. … I personally congratulate you Mr. Khamenei that you have served this nation in the frontlines in a military uniform and behind the battlefield in a clerical garb. I beseech God to bestow His goodness upon you so that you can continue to serve Islam and Muslims.”

The day after the attempt on Khamenei’s life, the terror campaign against the revolutionary regime escalated dramatically. On June 28, 1981, a powerful bomb tore through the IRP’s Tehran headquarters during a party leadership meeting. Over 70 people were killed in the blast, including many prominent figures, most notably Ayatollah Beheshti, the IRP’s Secretary General and Iran’s chief justice, who was the second-most powerful regime official behind Khomeini. Four other cabinet ministers and 27 IRP majles members were also among the casualties of the attack, which the regime attributed to the MEK.

The attack shook the regime’s confidence and increased its paranoia, as its adversaries had demonstrated the ability to penetrate the inner sanctum. All leading officials were suddenly potentially marked for death. The Khomeinists responded with increased repression of the MEK and other opposition elements, spurring further terror attacks. Over the next few months, the regime’s security and intelligence services undertook operations to disrupt the opposition’s ability to carry out further armed rebellion. Mass arrests increased, targeting operatives and intellectuals, journalists, artists, and ordinary demonstrators opposed to clerical rule. Whereas the regime had previously sought to obfuscate its human rights abuses, it began carrying out public executions and stepping up the mistreatment of prisoners at Tehran’s notorious Evin prison to deter rebellion through fear.

A month after Banisadr’s impeachment, Iran held a presidential election to replace him. For the first time, the Guardian Council vetted and disqualified candidates based on their loyalty to the revolution, whittling the field down to four from more than 70 applicants. All four candidates ran under the banner of the Islamic Republican Party, as other parties were effectively banned at this point. Rajai, who had served as prime minister during the Banisadr presidency, was elected with 90 percent of the vote in an election with a 64 percent voter turnout.

Just over a month into his term, on August 30, 1981, a bomb targeted a meeting of the government’s special security committee at the prime minister’s offices. President Rajai, his prime minister who had also succeeded Beheshti as Secretary General of the IRP, and the national chief of police were killed in the bombing. Rajai’s assassination was just the latest in the MEK-led ongoing terror campaign; various Friday prayer leaders around the country, provincial officials, the warden of Evin prison, and revolutionary court justices also lost their lives during this period. As security tightened around senior officials, the opposition also targeted lower-level officials, members of revolutionary organizations, and Revolutionary Guardsmen.