While his primary education focused mainly on traditional religious subjects, at the age of 13, Khamenei underwent a political awakening that led him to adopt Islamism, an ideology that merged politics and Islam, as his guiding principle. During that year, Khamenei attended a speech by the fundamentalist cleric Nawwab Safavi, who was later executed by the Shah’s regime for his militant activities. According to Khamenei, hearing Safavi’s “fiery speech against the Shah’s anti-Islamic and devious policies” sparked his initial “consciousness concerning Islamic, revolutionary ideas and the duty to fight the Shah's despotism and his British supporters.”

The following year, in 1953, a significant event occurred that further intensified Khamenei’s hostility toward the West, and the U.S. in particular. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the British Secret Intelligence Service collaborated with the Shah to launch a coup against Iran’s democratically-elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh. The coup was driven by concerns over the spread of communism and Mosaddegh’s push to nationalize Iran’s oil industry. Although the initial coup failed, the CIA orchestrated pro-Shah demonstrations that paved the way for his return to power. Mosaddegh was deposed and arrested and replaced with a more compliant prime minister.

The coup against Mosaddegh sparked a widespread anti-U.S., anti-U.K., and anti-imperialist sentiment among the Iranian public, including the clergy and the secular intellectuals. For Khamenei, it was the first major incident coloring his anti-American worldview. The intervention made it clear to him that the U.S. sought to dominate Iran and was hostile to any effort by Iranians to assert their independence or be governed in a truly democratic fashion. Khamenei has maintained these perceptions to the present day and firmly believes that U.S. policy towards Iran is focused on regime change, rather than simply behavior modification.

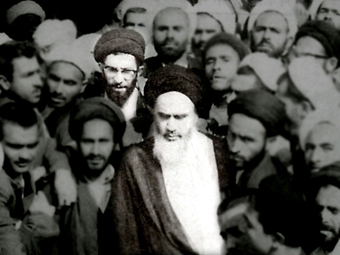

Khamenei finished his intermediate and advanced religious education in Mashhad and briefly visited Najaf in 1957 to pursue his advanced religious studies. Following his father’s wishes, Khamenei attended seminary studies in Qom from 1958 to 1964. It was in Qom, in 1962, that Khamenei first encountered Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who became Khamenei’s lifelong spiritual and political guide. According to Khamenei, all of Khomeini’s beliefs, worldview, and subsequent actions were the source of his devotion to Khomeini’s vision of Islam. At that time, Khomeini was not yet widely known in Iran, but he garnered popularity among the young seminarians in Qom due to his charisma and defiant opposition to the Shah. During this period, Khamenei also formed bonds with other disciples of Khomeini’s revolutionary ideology, including figures like Rafsanjani and the highly conservative cleric Mohammad Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi, who would later become part of the clerical elite and hold senior posts following the Islamic Revolution.

Under Khomeini’s guidance, Khamenei became active in protests against the Shah’s rule. Before the 1953 coup that replaced Prime Minister Mosaddegh, the Shah was considered a weak and indecisive leader more interested in womanizing and enjoying a lavish lifestyle than in governance. However, upon his return from exile, he became a more forceful leader, taking steps to sideline the new prime minister and consolidate his executive power. The Shah ruled Iran with an increased sense of purpose and ruthlessness, relying on his heavy-handed intelligence apparatus and secret police to suppress opposition.

During the 1960s, the Shah pursued his signature initiative, known as the White Revolution, which aimed to modernize and overhaul Iran comprehensively. The Shah presented himself as a progressive reformer, aiming to liberate Iran from reactionary forces, particularly the Shi’a clergy. In addition to large-scale infrastructure projects aimed at industrializing the country and land reforms intended to break up the wealth and political power of large landowners, the White Revolution focused in large part on reforming education and societal norms in Iran, placing the Shah in direct conflict with the clergy. The Shah’s actions, such as promoting an environment of night clubs and what some considered sexual freedom in Tehran and other Iranian cities, granting increased political rights to religious minorities, giving women suffrage and greater educational opportunities, and establishing private universities, were seen as an assault on the privileged status of the clergy and Islam itself, sparking opposition.

The Shi’a clergy, feeling their privileged status and Islamic values under attack, led the opposition to the Shah’s program of social, economic, and political reforms. They called on Iranians to resist the imposition of Western cultural influences and instead return to a traditional Islamic identity. Qom served as one of the primary centers of opposition activism, with its seminary students forming the core of the anti-Shah movement. Among the students, Ayatollah Khomeini emerged as the unifying leader of the opposition. Unlike other more quietist senior clerics, who opposed the Shah in rhetoric only, Khomeini viewed it as a religious duty to actively wage revolutionary struggle against the Shah’s regime.