Unmoved by the prevailing spirit of unity in the country, Banisadr and the IRP did little to temper their infighting during the early months of the conflict. Prime Minister Rajai sought to sideline Banisadr at every turn, prompting Banisadr to write a confidential letter to Khomeini in October 1980 appealing to him to dismiss Rajai and dismantle the IRP-dominated government, which he claimed was incompetent, lacked public support, and had declared war on his presidency. Using the war emergency as a pretext, the Khomeinists increased their repression within Iranian society, intensifying the ongoing Cultural Revolution and prosecuting the war on their opponents with the same vigor as the conflict against Iraq, shuttering newspapers and tamping down on dissent. The Khomeinist revolutionary komitehs, which Banisadr had sought to rein in, reasserted their presence, enforcing curfews and establishing patrols to monitor for “subversives.”

With his reform agenda frustrated, Banisadr sought to resolve his differences with the Rajai government. He also frequently began meeting with Ayatollah Khomeini to implore the Supreme Leader to mediate on his behalf. When this approach failed to yield progress, he went on the offensive against the IRP. Banisadr began traveling around the country, making speeches and holding rallies where he attacked his clerical rivals. He began writing a daily column in his newspaper where he openly aired his political grievances. In his columns, he compared the IRP’s dominance to the era of single-party rule under the Shah, labeled the Cultural Revolution as an attack on knowledge and expertise because the IRP had neither, and accused the Khomeinists of frequently engaging in torture, an emotionally fraught accusation given the torture many revolutionary leaders suffered under the Shah.

Banisadr’s incendiary attacks on the IRP were tantamount to sedition in the eyes of the Khomeinists. They responded by denigrating his loyalty to Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution and began using their informal power structures to censor and harass Banisadr and his allies. Club-wielding komitehs broke Banisadr’s speeches and rallies, and the IRGC and revolutionary courts escalated arrests and harsh punishments of opposition elements. According to scholar Shaul Bakhash’s historical account of the period, the Khomeinists “deliberately worked to sharpen the dispute into a struggle between Islam and secularism, the clerics and the Westernized intellectuals, revolutionary steadfastness and compromise, and ultimately, loyalty and disloyalty to the person of Khomeini.”

As the pressure campaign against Banisadr mounted, the MEK, an organization far to his left, increasingly allied with the beleaguered president. The MEK backed Banisadr’s calls for pluralism, free speech, and association, which they saw as necessary for their continued political survival. They saw in the moderate Banisadr a vehicle that could lead the radical group to more mainstream acceptance among the middle classes. The MEK mobilized its followers to attend Banisadr’s rallies, providing a force that could fight back against the komiteh’s attempts to violently break up these demonstrations. Still, the MEK’s opposition was fractious. Banisadr and his supporters among bazaari and conservative religious camps chafed against drawing too close to the MEK’s Marxist economics and calls for secularist governance.

While the MEK attempted to fight back against the komitehs, they were outmatched by the brutality of the club and switchblade-bearing Khomeinist partisans, which killed dozens of their opponents in street clashes around the country in the final months of Banisadr’s presidency. Banisadr continued to appeal to Khomeini to rein in this street justice. However, Khomeini and other IRP officials offered only feeble condemnations of hooliganism while blaming Banisadr for stoking the masses' anger. While Khomeini’s sympathies lied with his partisans, he did not fully break with Banisadr, as he still needed buy-in from Banisadr’s constituencies to keep the revolutionary regime afloat. As Banisadr drew closer to the MEK and increased his denunciations of Khomeini’s closest clerical allies and the excesses of the revolution, however, Khomeini’s support waned.

Khomeini made one final attempt to mediate the dispute between Banisadr and the IRP in March 1981. Khamenei was among the IRP leaders brought into the meeting, alongside heavyweights such as IRP Secretary General and Chief Justice Ayatollah Beheshti, Parliament Speaker Rafsanjani, and Prime Minister Rajai. After the meeting failed to yield progress, Khomeini reiterated his support for Banisadr as commander-in-chief and banned both sides from further speeches or articles that would contribute to factionalism. While ostensibly a neutral ruling, Khomeini took away Banisadr’s ability to press his case to the populace, forcing him to silently acquiesce to being a figurehead president with all the real power in IRP control. Convinced of his popularity, Banisadr soon resumed public denunciations of the IRP in his newspaper and at demonstrations, increasingly challenging Khomeini’s authority directly. After calling on his supporters to resist the revolutionary regime’s slide to dictatorship, tantamount to calling for an uprising, Khomeini finally withdrew his support for Banisadr. On June 7, 1981, his newspaper was banned; days later, Khomeini stripped him of his role as commander-in-chief.

Having finally lost Khomeini’s support and recognizing that the IRP was increasing its repression of opposition elements, Banisadr hid. Rafsanjani initiated impeachment proceedings against him in the majles on June 20 and 21, 1981. By this time, arrests and executions of his aides and violent crackdowns on his backers had begun in earnest. As the majles debated, hostile crowds outside chanted “Death to Banisadr,” vowing retribution against any legislators who defended him. Given the charged atmosphere, only a handful of the 40-45 members who supported Banisadr’s agenda dared speak in his favor. Banisadr was overwhelmingly impeached and removed from office, with only one member voting against the action and several more abstaining.

The elimination of Banisadr proved an insurmountable setback for the loose coalition of moderate and leftist forces in the country. In the run-up to his impeachment, the MEK and the National Front had organized what they hoped would be mass demonstrations of support for Banisadr and against the IRP. However, these failed to move the needle, especially as many sympathetic to their ideologies opted not to take to the streets over fears of Khomeinist club-wielding hooligans. On the actual day impeachment proceedings began, the MEK, backed by almost all other opposition groups, called for Iranians to march against dictatorship, which according to Baqer Moin, was “the most direct challenge to Khomeini since the revolution, and an unmistakable attempt to overthrow the religious establishment.” The IRGC joined forces with the Khomeinist komitehs to suppress the demonstrations, opening fire on the crowd in Tehran, arresting hundreds, and reportedly carrying out summary executions of MEK supporters on the spot.

Following his impeachment, Banisadr issued calls for a mass uprising from hiding. Khomeinist forces, meanwhile, continued suppressing ongoing, sporadic MEK-led demonstrations, leading the group to change tactics in favor of armed rebellion. Banisadr opted to fully embrace the MEK at this point and entered into a formal alliance with the group. A month later, Banisadr and the MEK’s leader, Masud Rajavi, fled Iran and settled in Paris, where Banisadr was an advisor to Ayatollah Khomeini before the Revolution. This time around, Banisadr and Rajavi would work to overthrow Khomeini, creating the National Council of Resistance, an umbrella group for Iran’s beleaguered opposition factions to coordinate their anti-regime activities and plans for governance if they succeeded in toppling the Islamic Revolution.

Banisadr’s impeachment touched off an era of guerilla warfare between liberal and leftist forces led by the MEK and the Khomeinists. The MEK’s strategy was first to destabilize the regime by assassinating key leadership, then crippling it through large-scale demonstrations and strikes that it hoped would lead to a mass uprising and regime overthrow. The MEK’s assassination campaign would eliminate many of the key figures within the IRP, some of whom presumably would have been ahead of Khamenei in the queue for the prime leadership roles he went on to obtain.

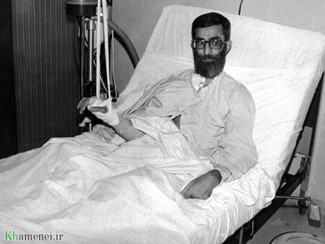

Ali Khamenei was the first figure targeted in the assassination campaign. On June 27, 1981, Khamenei returned to Tehran from one of his sojourns to the Iran-Iraq War battlefield as Khomeini’s representative on the Supreme Defense Council. While delivering a speech at the Abuzar Mosque in southern Tehran, a bomb placed in a tape recorder on the table before him detonated, gravely wounding Khamenei. In his telling, his pulse briefly stopped following the blast. Khamenei was hospitalized for 42 days and suffered hearing loss, lung and vocal cord damage, and permanently lost the use of his right arm. According to a relative who grew up with Khamenei, the bombing changed Khamenei and “made him deeply angry inside – it gave him a grudge against people.” It is unclear which faction was behind the bombing; it was initially attributed to the Forqan group, a militant Shi’a organization opposed to the existence of clergy. However, today, Khamenei and the regime allege that the MEK was behind the plot in their propaganda materials.

Khamenei’s miraculous survival enhanced his prestige in Khomeinist circles, and he came to be seen as a “living martyr.” Ayatollah Khomeini sent Khamenei a note filled with fulsome praise, showing the high esteem in which he held his protégé, in which he declared, “Today the enemies of Islam have carried out an assassination attempt on you, the one who is from the genealogy of the tribe of Imam Hossein, the son of ‘Ali. You have done nothing but serve Islam and this country. You have been a faithful soldier at the frontlines, and a passionate teacher for the public. … I personally congratulate you Mr. Khamenei that you have served this nation in the frontlines in a military uniform and behind the battlefield in a clerical garb. I beseech God to bestow His goodness upon you so that you can continue to serve Islam and Muslims.”

The day after the attempt on Khamenei’s life, the terror campaign against the revolutionary regime escalated dramatically. On June 28, 1981, a powerful bomb tore through the IRP’s Tehran headquarters during a party leadership meeting. Over 70 people were killed in the blast, including many prominent figures, most notably Ayatollah Beheshti, the IRP’s Secretary General and Iran’s chief justice, who was the second-most powerful regime official behind Khomeini. Four other cabinet ministers and 27 IRP majles members were also among the casualties of the attack, which the regime attributed to the MEK.

The attack shook the regime’s confidence and increased its paranoia, as its adversaries had demonstrated the ability to penetrate the inner sanctum. All leading officials were suddenly potentially marked for death. The Khomeinists responded with increased repression of the MEK and other opposition elements, spurring further terror attacks. Over the next few months, the regime’s security and intelligence services undertook operations to disrupt the opposition’s ability to carry out further armed rebellion. Mass arrests increased, targeting operatives and intellectuals, journalists, artists, and ordinary demonstrators opposed to clerical rule. Whereas the regime had previously sought to obfuscate its human rights abuses, it began carrying out public executions and stepping up the mistreatment of prisoners at Tehran’s notorious Evin prison to deter rebellion through fear.

A month after Banisadr’s impeachment, Iran held a presidential election to replace him. For the first time, the Guardian Council vetted and disqualified candidates based on their loyalty to the revolution, whittling the field down to four from more than 70 applicants. All four candidates ran under the banner of the Islamic Republican Party, as other parties were effectively banned at this point. Rajai, who had served as prime minister during the Banisadr presidency, was elected with 90 percent of the vote in an election with a 64 percent voter turnout.

Just over a month into his term, on August 30, 1981, a bomb targeted a meeting of the government’s special security committee at the prime minister’s offices. President Rajai, his prime minister who had also succeeded Beheshti as Secretary General of the IRP, and the national chief of police were killed in the bombing. Rajai’s assassination was just the latest in the MEK-led ongoing terror campaign; various Friday prayer leaders around the country, provincial officials, the warden of Evin prison, and revolutionary court justices also lost their lives during this period. As security tightened around senior officials, the opposition also targeted lower-level officials, members of revolutionary organizations, and Revolutionary Guardsmen.

The tumultuous Banisadr presidency and subsequent declaration of war by the opposition against the revolutionary regime eliminated whatever trepidation Ayatollah Khomeini previously had about the clergy appearing to monopolize political power and implement a theocracy in Iran. He now encouraged his clerical followers to take a more hands-on role in all administration matters and to run for higher office. Secular experts and technocrats were pushed out of key decision-making jobs throughout the government, as Khomeini now opined that as an inherently political religion, clerics learned in Islamic jurisprudence were the most qualified to run all aspects of statecraft and bureaucracy, as they were the only figures who could ensure that all decisions complied with Khomeini’s revolutionary Islamism. As a result of Khomeini’s decrees, clerics came to play a pervasive role in daily life in the Islamic Republic, forming an extensive network of Khomeinist representatives who increased the clergy’s control to near totalitarian levels. Every public institution – the courts, schools and universities, local government offices, and workplaces – was dominated by the Khomeinist clergy, creating a system far more pervasive and repressive of individual liberties than the Shah’s regime.

Khomeini publicly intoned that clerics could uniquely be entrusted with the highest positions of authority, as they did not seek personal glory or power, but rather, were vessels concerned only with ensuring the supremacy of Islam. In one speech justifying greater clerical involvement, Khomeini stated, “I have brought them up. I brought up Beheshti, Khamenei, and Rafsanjani. They are not monopolistic. Of course, they want the monopoly of Islam.” In another speech, Khomeini spoke of the importance of clerics serving at every state level, saying, “For as long as we have no competent people to do the job, the clergy should stay in their positions. It is below the dignity of a clergyman to be a president or to occupy other posts. He does it because it is a duty. We have to implement Islam and should not fear anyone.”

With the spate of assassinations of senior IRP officials, including President Rajai and his prime minister, Mohammad-Javad Bahonar, clearing the path, the surviving party elites appointed Ali Khamenei as secretary general of the IRP and shortly after that asked him to run for president. Khamenei’s political activism in support of Khomeini’s revolutionary Islamism during the Shah’s reign and his fulfillment of various lower-level duties following the Islamic Revolution gradually elevated his stature within the IRP. It had shown he was a committed and willing functionary. He was by no means an innovative religious or political thought leader, which made him a suitable choice for the still-largely ceremonial role of president. The Khomeinist framers of the Islamic Republic’s Constitution, who were insecure as they were not fully in power at the time, had designed the presidency to give the public the sense that they had input into shaping their destiny but purposely made the position weak, so that no president could challenge the supremacy of the faqih. Banisadr’s presidency gave the system a stress test, but it functioned as designed, ensuring he was powerless to rein in clerical control and enact his reform-minded agenda.

Still recovering from his injuries sustained in the June 27, 1981 assassination attempt, Ali Khamenei reportedly demurred at the offer of the presidency, saying he would not be able to devote sufficient energy to the role due to his ill health. His colleagues allegedly responded, “That is why we are offering you the post.” As such, Khamenei brought stability to the presidency for the first time after the revolution. He served two terms as a largely subservient president who outwardly framed his role as helping enact Supreme Leader Khomeini’s vision. The tensions between the Iranian government’s republican and theocratic elements, which reared their head during every other presidential administration, were notably muted during Khamenei’s tenure. When he did have differences of opinion with Khomeini or chafed over his lack of influence, he would seek out the more established and powerful Rafsanjani to appeal to Khomeini on his behalf for more authority.