Who Will Be Iran's Next Supreme Leader?

Download PDFConstitutional Underpinnings

Iran’s constitution provides broad guidance on the characteristics sought in candidates for the position of supreme leader. Article 5 stipulates that the ideal individual be: “just, pious, knowledgeable about his era, courageous, a capable and efficient administrator…” Article 109 elaborates that the individual should have “[s]cholarship, as required for performing the functions of religious leader in different fields; required justice and piety in leading the Islamic community; and right political and social perspicacity, prudence, courage, administrative facilities, and adequate capability for leadership.” It’s this conglomerate of religious, administrative, and political qualities that will prove pivotal in determining the right figure for the job.

When the supreme leader dies or is incapacitated, the Assembly of Experts is constitutionally charged with selecting his successor. It’s possible that in the interim, Iran will form a leadership council comprised of officials like the head of the judiciary, the president, and a member of the Guardian Council selected by the Expediency Council, while the key stakeholders in succession—like the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Shiite clergy—build consensus.

The Iranian people elect members—88 Islamic jurists—to the Assembly of Experts every eight years and it has a leadership board and six subcommittees. There is a subcommittee within the Assembly which oversees the work of the supreme leader—but its actual authority to provide oversight remains in question given the singular power of the supreme leadership in Iran.

Precedent

In 1989, when the last succession process took place, the Islamic Republic found itself in a challenging situation. Ruhollah Khomeini had spent much of his decade in power with a designated successor—Hussein-Ali Montazeri. It was Montazeri who had the requisite clerical standing—grand ayatollah—to be considered the rightful heir to the Khomeini legacy. But Montazeri had a series of disagreements with Khomeini over politics and policy, resulting in Khomeini questioning even his religious credentials. Because of this rupture, when Khomeini died in 1989, Iran was without an heir apparent.

The first choice among many in the Assembly of Experts was Seyyed Mohammad Reza Golpayegani, a grand ayatollah and one of the most revered senior Shiite clerics in Iran. But Golpayegani fell short of the necessary support from the Experts. The Islamic Republic even briefly considered forming a leadership council comprised of figures like then-President Ali Khamenei, the head of the Assembly of Experts Ayatollah Ali Meshkini, and the head of the judiciary Abdul-Karim Mousavi Ardebili. Finally, then-Speaker of Parliament Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani put his finger on the scale in favor of Ali Khamenei as Khomeini’s successor.

Many in the clerical establishment felt Khamenei would be a placeholder appointment. A video of the Assembly of Experts recently resurfaced, which indicates that Khamenei was only supposed to be supreme leader temporarily—for one year—due in part to his inferior religious credentials as a hojatolislam, rather than as an ayatollah. As Khamenei himself admitted in 1989, “based on the constitution, I am not qualified for the job and from a religious point of view, many of you will not accept my words as those of a leader.” Khamenei became the permanent officeholder after the passage of constitutional amendments that reduced the religious qualifications required to assume the supreme leadership.

As of January 2019, according to Iranian media reports, the Assembly Experts has formed a committee to vet candidates for the next supreme leadership. Only current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has access to the dossiers compiled by the committee. There is also a committee that has been empaneled to examine potential candidates for a deputy supreme leader, but it is unclear if the Iranian system has made a decision to pursue this option to date. Given Montazeri’s experience, Khamenei is likely wary of publicly anointing such a figure.

Candidates

This resource is divided into first, second, and third tier candidacies for the supreme leadership. UANI has decided to designate individuals as first tier contenders because they have significant administrative experience or power in the Islamic Republic, and all hold an equivalent or higher religious rank as compared to Ali Khamenei at the time he ascended to the supreme leadership. UANI defines second tier aspirants as those lacking wide-ranging administrative experience but may eventually enter the decision-making equation through familial connections, public profile, or membership or leadership within state organs. UANI defines third tier candidates as dark horses—those clerics with a more limited public profile but who command consideration by virtue of their ties to the current supreme leader or a position within Iran’s religious hierarchy. Candidates who are older than the current supreme leader—like longtime Secretary of the Guardian Council Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati—have not been included, given the uncertainty of their longevity and the likelihood that the Islamic Republic will want its third supreme leader to serve for at least a decade, as did Ruhollah Khomeini from 1979-89.

First Tier Candidates

Mojtaba Khamenei

Mojtaba Khamenei, born in 1969, is the second oldest child of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. His wife is the daughter of former Speaker of Parliament Gholam-ali Haddad-Adel. Some Iranian media refers to him as a hojatoleslam, others as an ayatollah. Observers describe him as a “gatekeeper” for his father, similar to Ahmad Khomeini’s role for his father, Ruhollah Khomeini. According to leaked U.S. State Department cables, these same reports consider Mojtaba second-only to Mohammad Golpayegani, the head of the Office of the Supreme Leader. The U.S. government confirmed his importance within the Supreme Leader’s Office in November 2019, when he was sanctioned. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, “[t]he Supreme Leader has delegated a part of his leadership responsibilities to Mojtaba Khamenei, who worked closely with the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF) and also the Basij Resistance Force (Basij) to advance his father’s destabilizing regional ambitions and oppressive domestic objectives.”

While occupying no official position in the Islamic Republic, officials have often portrayed him as an enigmatic kingmaker in Iranian electoral politics, interfering in both the 2005 and 2009 elections. Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of the Iranian parliament and then a candidate for president, alleged that Mojtaba had provided crucial backing to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005 after initially backing Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, causing Ahmadinejad’s rise in the first round of balloting. In 2009, reports claimed Mojtaba engineered Ahmadinejad’s victory and even instructed the Basij to aggressively clamp down on Green Movement demonstrators. In 2009, the British government froze a bank account rumored to belong to Mojtaba containing $1.6 billion, allegedly used to buy equipment for the Basij.

Despite the familial ties to Ayatollah Khamenei, Mojtaba will likely encounter religious, political, and administrative obstacles to becoming supreme leader. Opponents will seize on reports that he doesn’t hold the rank of an ayatollah. Politically, Mojtaba doesn’t have a natural constituency. This will make it difficult for Mojtaba to argue he has the “capability for leadership.” But with President Ebrahim Raisi’s death in 2024, this will position him prominently as a first-tier candidate. Mojtaba’s support within the IRGC could figure in his favor. There have also been unofficial attempts to increase his popularity as a potential supreme leader, with posters recently being found in Tehran promoting his candidacy. Administratively, while Mojtaba has experience working in the shadow of his father, learning at his feet, and being second-in-command in the Supreme Leader's Office, he lacks experience overseeing one branch of government. Even more challenging, Mojtaba is not an official member of a stage organ like the Guardian Council, Assembly of Experts, or the Expediency Council to compensate for his administrative shortcomings.

This is not to mention that Mojtaba has angered elements of the IRGC with his intervention in state affairs. There may be resistance to his assuming power from his father, particularly among those who argue that such a dynamic mirrors a hereditary monarchy that the Islamic Revolution overthrew in 1979.

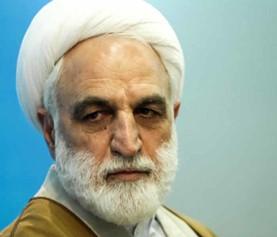

Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei

Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei, born in 1956, is a hojatolislam, although some reports refer to him as an ayatollah. Mohseni Ejei has spent his career in Iran’s judiciary and intelligence apparatuses—he served as a minister of intelligence under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, attorney-general, and first deputy chief of and spokesman for the judiciary. He is currently chief justice, with Iran’s supreme leader naming him to the post in 2021.

Significantly, Ahmadinejad fired Mohseni Ejei as minister of intelligence due to his perceived closeness with the supreme leader after a disagreement over Ahmadinejad’s choice for first vice president, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei. Many leading clerics also consider Mashaei as questioning of and undermining their role in Iran. However, the judiciary, an organ under the complete control of Ayatollah Khamenei, quickly took Mohseni Ejei under its wing.

The U.S. government sanctioned Ejei in 2010 for his role in suppressing unrest during the Green Movement of 2009. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, “Mohseni Ejei has confirmed that he authorized confrontations with protesters and their arrests during his tenure as Minister of Intelligence. As a result, protesters were detained without formal charges brought against them and during this detention detainees were subject to beatings, solitary confinement, and a denial of due process rights at the hands of intelligence officers under the direction of Mohseni Ejei. In addition, political figures were coerced into making false confessions under unbearable interrogations, which included torture, abuse, blackmail, and the threatening of family members.” Mohseni Ejei also stands accused of biting a journalist during a fight at a meeting of a press advisory council in Iran. As Radio Free Europe found in 2009, Mohseni Ejei’s website even included the infamous incident in his official biography at one point.

Mohseni Ejei served as deputy chief justice under both Ebrahim Raisi and his predecessor. There are reports that Mohseni Ejei did not get along with Raisi—Raisi never had the chance to play a role in selecting his own new deputy chief justice during his time as chief of the judiciary.

Religiously, Mohseni Ejei has the requisite religious qualification, given he is a hojatolislam—a similar ranking that Khamenei held upon his ascension as supreme leader. Politically, Mohseni Ejei has developed a public following given his high-profile appointments within the Islamic Republic. Additionally, Ahmadinejad removing him from his post as intelligence minister may be attractive to many in the clerical establishment, given their distrust of the former president. However, Mohseni Ejei does have political baggage as he is one of the most feared members of the Iranian establishment. Administratively, Mohseni Ejei’s role as chief justice positions him as a potential contender for the supreme leadership given that many of his predecessors themselves have been considered candidates over the last few decades. The chief justice also plays a constitutional role on an interim leadership council—should one be formed upon Khamenei’s death—and has a seat on the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC). Thus, this provides Mohseni Ejei with a significant platform institutionally. Mohseni Ejei’s path to power is similar to that of Ebrahim Raisi—holding the positions of attorney-general, deputy chief of the judiciary, and finally chief justice. However, Raisi had a superior resume given his command of two—not just one—branches of Iran’s state. With Raisi out of the running for the supreme leadership after his death, attention will turn naturally to the incumbent chief justice.

Alireza Arafi

Alireza Arafi, born in 1959 in Meybod, has held a series of positions in the Islamic Republic of Iran. His family reportedly has Zoroastrian roots and later converted to Islam in the 19th century. According to Iran scholar Alex Vatanka, Arafi’s father Mohammad Ebrahim Arafi had a personal relationship with the founder of the Islamic Republic Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Arafi’s rise tracks with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s ascension to the post in 1989.

Arafi began his career as a Friday Prayer leader in Meybod in 1992. He later rose to become Friday Prayer leader in the holy city of Qom, a critical center of religion in the Islamic Republic. Among the other positions Arafi has held includes chairman of Al-Mustafa International University, which is subject to U.S. counterterrorism sanctions for serving as an intelligence recruitment center for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force. The IRGC has used Al-Mustafa International University to recruit for its Fatemiyoun and Zaynabiyoun Brigades for combat in Syria. As head of Iran’s Seminary, Arafi has also spearheaded a push to “Islamize” Iran’s university and seminary system. When he was head of the Office for Cooperation between Clergy and Hawza, he led the charge to replace standard humanities textbooks with Khomeinist versions. During his tenure at the Imam Khomeini Educational and Research Institute, which was led for many years by the late Ayatollah Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi—himself once considered a contender to succeed Khamenei—Arafi likely increased his stature and expanded his network through his actions and contributions.

Despite losing an election for a seat on the Assembly of Experts in 2016, in 2019, Khamenei named him to the Guardian Council, where he replaced Mohammad Momen, a moderate conservative. Arafi has played a key role in vetting candidates for state elections and parliamentary legislation, diversifying his resume and adding political heft.

Iran’s supreme leader has also named him as a member of the Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution in Iran. It is responsible for “expansion and promotion of the influence of Islamic culture in the society…purification of scientific and cultural establishments from materialistic ideas and clearing the country’s cultural environment from manifestations of Western influence, and development of universities, schools, and cultural and art centers in accordance with the righteous Islamic culture.” Arafi is also now the second deputy chairman of the Assembly of Experts. Thus, he is not only at the center of academic and religious life in the Islamic Republic, but he is also now embedded in its political affairs.

Arafi has a predominantly academic, religious, and administrative profile in the Islamic Republic. This is especially true given his leadership over Iran’s Seminaries. Politically, his seat on the Assembly of Experts has helped build him a profile, as has him being one of the supreme leader’s appointees on the Guardian Council. Arafi has likely built goodwill with the IRGC through his stewardship of the Al-Mustafa International University as well. He has been a reliable conservative regime messenger, saying “America will take its wish for Iran to abandon production of military hardware to the grave.” In one Friday Prayer sermon in 2019, he pledged “We will stay with our imam and leader to the end, when we humiliate [global] arrogance. Together with the Sayyed of the resistance we say: Oh great leader of the world of Islam, we will be with you until the end, when the arrogant people in the world are defeated, and Israel is erased.”

One weakness in his candidacy for the supreme leadership, however, is him not being a Sayyed, or a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. Khamenei is a Sayyed, as was Khomeini. Yet this may not necessarily be a dealbreaker as Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali-Montazeri, when he was initially named as Ruhollah Khomeini’s deputy supreme leader, was also not a Sayyed. Although Montazeri’s status as a grand ayatollah likely compensated for that gap in his pedigree.

Second Tier Candidates

Hashem Hosseini Bushehri

Ayatollah Seyyed Hashem Hosseini Bushehri, born in 1956 in Bardkhun, Bushehr, is a powerful figure in Iran's religious and academic spheres. He embarked on his theological education in Bushehr before moving to Qom to further his studies under esteemed Islamic scholars such as Ayatollah Golpaygani and Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi. His dedication to jurisprudence and seminary sciences is evident from his extensive academic journey, where he studied texts like "Treatises" and "Kifayya" under prominent teachers. Ayatollah Bushehri's scholarly pursuits were complemented by practical involvement during the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, where he played a pivotal role in distributing Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's leaflets despite facing multiple arrests and interrogations.

In his administrative career, Bushehri held numerous significant positions within Iran's seminaries. He served as the head of the Qom Seminary for multiple terms, demonstrating a solid commitment to managing and promoting Islamic education nationwide. According to reports from July 11, 2012, he was appointed the head of the Qom Seminary after extensive deliberations by the Supreme Council of the Seminary of Qom. His tenure was marked by proactive initiatives, such as formulating the Revolutionary Seminary plan in response to directives from the supreme leader, showcasing his organizational insight and leadership in educational reforms.

Bushehri has been an influential voice in Iranian politics and society throughout his career. In late April 2023, during his Friday sermon in Qom, he critiqued government policies, stating, "Decisions made in those meetings should be followed up seriously by executive officials." He also addressed economic challenges, emphasizing the need for stable monetary policies amidst inflation and currency devaluation. His statements reflected concern over Iran’s labor problems, particularly on Labor Day, when he called for legal support measures amid strikes and protests in industrial centers.

Despite his tenure, Bushehri's leadership in the seminaries concluded with his seventh term, despite widespread calls for his continuation. His decision not to prolong his role was influenced by considerations at various levels of the seminary, including his role as a member of the Assembly of Experts and the presidium of the Islamic Republic Parliament. His departure marked the end of a period where he had previously served as the head of the Seminary of Qom for ten consecutive periods.

Bushehri's influence extends beyond national borders, encompassing roles in international Islamic organizations and educational institutions. Like Alireza Arafi, he was a member of the board of trustees of Al-Mustafa International University and the World Center for Islamic Sciences. The supreme leader appointed him for his expertise and leadership in Islamic education. His scholarly contributions are extensive, with works ranging from jurisprudential texts to commentaries on Islamic principles and interpretations of Quranic verses.

In May 2024, Bushehri made headlines again with his remarks on women's rights, arguing against Western views and urging Iranian women to "address issues such as the status of women's rights in Western societies and the flaws that exist in this area in the West," which would prevent the "enemy [the West]" to "not even have a chance to challenges us [Iran]." His statements came amidst international scrutiny of Iran's treatment of women, sparked by protests and movements advocating for greater freedoms. As a prominent religious leader and educator, Ayatollah Hashem Hosseini Bushehri continued to shape discourse within the Islamic Republic, combining his Islamic scholarship with his leadership to navigate political challenges and uphold the regime's Islamic principles.

As the first deputy chairman of the Assembly of Experts, Hashem Hosseini Bushehri will likely have a leadership role during the next succession after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei passes away. Politically, his experience on the Assembly of Experts enhances his candidacy. Administratively and religiously, his managerial role of the Qom Seminary and his status as an ayatollah qualifies him. But Hashem Hosseini Bushehri lacks experience heading major branches of government, which may impede his chances.

Mohsen Qomi

Mohsen Qomi, a close confidant of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and deputy advisor for international affairs, has a significant presence in Iran’s political landscape. He is also known for his nearly 20-year tenure at the Assembly of Experts, the body responsible for selecting the supreme leader. Born in the village of Mamazand in Varamin near Tehran in 1960, he began religious studies at the Qom Seminary at age 11. During the Iran-Iraq War, Qomi was wounded during the 1981 siege of Abadan and lost three brothers and a nephew, and his mother was killed during the 1987 Mecca clashes.

Qomi’s current role often involves representing the supreme leader on official international visits. Over his career, Qomi has frequently been Khamenei’s appointee in various roles, including membership on the Board of Trustees of the Islamic Propaganda Office of the Qom Seminary. In 1999, following a recommendation by Ahmad Jannati, he was appointed president of the Supreme Leader’s Representative Office for Universities, a role he maintained until 2005.

Qomi was at the forefront of the regime’s efforts against the pro-democracy student movement during his university tenure. The Office of the Supreme Leader played a vital role in this conflict, alongside the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), its Basij paramilitary, the police, and the Ministry of Intelligence. These experiences provided Qomi with direct involvement in suppressing dissent. He shares Khamenei’s strong interest in the cultural war against the West, reflecting their shared ideological views. From 1996 to 1998, he directed the “Encyclopedia of Islamic Rational Science,” a project published by the Imam Khomeini Education and Research Institute, which was led by the radical cleric Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi.

Qomi’s diplomatic demeanor fostered a good relationship with President Hassan Rouhani, who considered him to lead the Ministries of Intelligence and Culture and Islamic Guidance. However, Khamenei preferred to keep Qomi in his office, deeming his role “very important.” Since 1998, Qomi has been a member of the Assembly of Experts, a body he describes as accountable only to God in their decisions. Within the Assembly, he serves on Commission 111, which theoretically monitors the supreme leader’s adherence to Islamic principles. Qomi has also served on the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, the Board of Trustees of the Propaganda Office of the Qom Seminary, and the Press Supervisory Board.

Qomi is recognized as a “hardliner’s hardliner,” evidenced by his extreme views and statements. He has referred to Israel as “a cancerous tumor” that should be eradicated and has staunchly defended Iran’s military intervention in Syria. His role as a foreign affairs aide often takes him to crucial countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, and Russia, representing Khamenei’s interests. His extensive tenure in Khamenei’s office, direct access to the supreme leader, and influential position in international affairs place him in a comfortable position as Khamenei’s successor.

However, his candidacy’s weaknesses include not being a Sayyed, or a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, as Khamenei is. Qomi also lacks a significant public political profile and the administrative and bureaucratic experience of other candidates. Likewise, he is only a hojatoleslam and not an ayatollah.

Mohsen Araki

Ayatollah Mohsen Araki was born in Najaf in 1955 into a well-educated family deeply rooted in Islamic scholarship. His father, Ayatollah Haj Sheikh Habibollah Araki, was a renowned jurisprudent in the Najaf seminary, following the scholarly legacy of his father, Ayatollah Sheikh Safar Ali Araki. Ayatollah Sheikh Safar Ali Araki was a prominent instructor at the Najaf Seminary. Growing up in such an environment, Ayatollah Mohsen Araki received his early education in Quranic studies and foundational texts from his parents before attending the Montadi Al Nashr school for further Arabic and elementary education studies.

Ayatollah Araki began his formal seminary education in 1968, initially learning from his father and then studying under several notable seminary instructors. By 1974, he had advanced to the Feqh class of Ayatollah Khoei and later attended the courses of Ayatollah Muhammad Baqer Sadr. Political pressures from the Ba’ath government in Iraq forced him to relocate to Qom in 1975. In Qom, he continued his advanced studies under Ayatollah Mirza Kazem Tabrizi and Ayatollah Vahid Khorasani, among others. Additionally, Ayatollah Araki studied Islamic philosophy, including works by Hegel, under Ayatollah Beheshti and participated in various scientific and cultural activities, establishing numerous educational and charitable institutions.

Numerous influential positions within the Islamic Republic of Iran mark Araki’s career. His career began in 1980 as a judge at the Islamic Revolutionary Courts of Abadan and Khorramshahr, and he soon became the head of these courts in Khuzestan in 1981. By 1982, he was appointed chief justice of Khuzestan Province, a position he held until 1983. From 1986 to 1989, he served as the representative of the Supreme Leader and Friday Prayer Imam in Dezful. Concurrently, he acted as the Sharia judge on the board for land transfers in Khuzestan from 1983 to 2004. In 1983, Araki founded the military wing of the Supreme Assembly of the Islamic Revolution of Iraq, later known as the Badr Corps, following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran in 1980. Araki’s influence extended into academia when he was appointed the representative of the Supreme Leader at Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz from 1990 to 1995. His roles also included being a member of the Assembly of Experts between 1990 and 1994, and from 1995 to 2004, he led the Islamic Center of England and established numerous other Islamic centers throughout England.

As head of the Islamic Revolutionary Courts of Khuzestan, Araki was implicated in numerous cases of torture, murder, extrajudicial executions, and summary trials; following the violent clashes on May 30, 1979, known as ‘Black Wednesday,’ many Arab activists were arrested and sentenced to death or long prison terms during expedited trials under his oversight. Kosar Al-Ali, a former political prisoner, recounted how Araki played a pivotal role in issuing death sentences for dozens of Arab activists: “Within an hour or two, they were all tried and told that they were sentenced to death. Tiz-Maghz was the Prosecutor, and Araki was the Sharia Judge.” Testimonies like that of Mansour Asl-Sharhani, a political prisoner from 1982 to 1988, highlight Araki’s direct involvement in the brutal judicial process. Asl-Sharhani detailed the torture methods he endured, describing how prisoners were subjected to severe beatings and other forms of physical abuse, with Araki’s knowledge and sometimes presence. Araki’s summary trials were notorious for lacking due process, often condemning multiple individuals within minutes. “They tried 30 people in one minute,” Asl-Sharhani recalled, emphasizing Araki’s sentences’ arbitrary and harsh nature.

In an interview with Fars in 2019, Araki, a member of the Fifth Assembly of Experts, revealed that the selection process for the supreme leader’s potential successors is shrouded in secrecy. According to Araki, a special “Commission of Inquiry” identifies individuals eligible for leadership, compiling their names into a confidential list. This list is so secretive that even the Assembly of Experts can only suggest candidates without knowing the full details. Araki said that the list would be reviewed, and those considered qualified for future leadership would be “registered in a very secret and confidential manner,” ensuring that the Assembly of Experts can access it only when necessary to evaluate the candidates.”

Araki further disclosed that only three people are privy to the supreme leader’s choices. He explained that due to past issues with publicly announcing a deputy leader, the decision was made to keep the number of those in the know to a minimum. He stated, “It has been decided in the special commission that exists that only three people should keep these names with them,” highlighting the extreme confidentiality measures in place to prevent leaks or unauthorized disclosures.

Araki lacks the administrative experience of other candidates. He does not maintain a significant public political profile and is not a Sayyed, or a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, as Khamenei is. But he is an ayatollah and his long experience on the Assembly of Experts and in the Islamic Republic’s religious hierarchy should not be discounted.

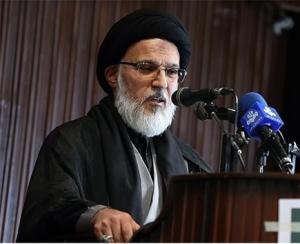

Ahmad Khatami

The cleric Ahmad Khatami was born in 1960. Khatami’s rise began in 1999 after winning a seat on Iran’s Assembly of Experts, and continued when Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei appointed him as Tehran’s substitute Friday Prayer Leader in 2005. It’s from this religious platform that Khatami built his brand—one of fire, fury, and fight.

Early on in his tenure as a Friday Prayer leader in 2006, his remarks in reaction to the Pope giving a speech in Germany that many found offensive to Muslims drew international attention. Khatami said “[t]he pope should fall on his knees in front of a senior Muslim cleric and try to understand Islam so he would never again say such absurd remarks.” At the same time, Khatami has used the tenets of Christianity as a means to attack America. Recently, he remarked, “I send my blessings to the Christians throughout the world, and I say to them: protect the honor of Christ. Unfortunately, the arrogant leaders who consider themselves Christians – and Trump says he hasn’t read anything but the New Testament all his life – bring disgrace upon this great prophet [Jesus]. [The Christians say:] Tell us what to do. [The Christians should] renounce America in a loud voice, and, like the [Iranian] people, they should say: “Death to America!”

Khatami has also engaged in bombastic international taunts. He routinely threatens Israel, recently warning “[t]he holy system of the Islamic Republic will step up its missile capabilities day by day so that Israel, this occupying regime, will become sleepless and the nightmare will constantly haunt it that if it does anything foolish, we will raze Tel Aviv and Haifa to the ground.” Khatami also brags about Iran’s nuclear prowess even under the auspices of the nuclear deal. In February 2019, Khatami claimed Iran “has the formula for building a nuclear bomb.”

The cleric has also cautioned the Iranian public about the dangers of Westoxification in Iran: “[T]oday they talk about legalizing alcoholic drinks, tomorrow they will say freedom of hijab, and the day after they will say we should have a referendum on the Islamic aspect of the regime. Know that you will take these dreams to your grave.” It’s this formula of using his clerical platform for headline-grabbing, hair-raising, shock value commentary that has endeared him to hardliners in the Iranian regime’s establishment.

Following the 2022 Iranian protests after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini at the hands of the Islamic Republic’s morality police, Khatami addressed the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) forces and police units, emphasizing that the preservation of the Islamic Republic was “one of our obligations.” The member of the Islamic Republic’s Assembly of Experts also praised the Basij paramilitary forces for their brutal crackdowns against peaceful Iranian protesters, stating that they were “persecuted” during the 2022 protests and “sacrificed their lives so that the Islamic Republic would pass through this stage.” Khatami has since been sanctioned by the European Union.

In 2016, Khatami won a leadership role on Iran’s Assembly of Experts as secretary of its board of directors. Such a promotion put Khatami in a key role to influence the succession process. In a sign that Iran’s supreme leader continues to value his loyalty, he named Khatami as a member of the Guardian Council in November 2020. Such a promotion has increased Khatami’s profile and importance within the system.

Religiously, Khatami’s rank as a hojatolislam wouldn’t disqualify him from consideration. Some Iranian news accounts even rank him as an ayatollah. Politically, Khatami’s voluminous record of public pronouncements on all kinds of matters of state leaves behind a paper trail with supporters and detractors alike. However, his lack of administrative experience in overseeing major institutions of state will hamper his candidacy.

Mohammad-Reza Modarresi Yazdi

Mohammad-Reza Modarresi Yazdi, born in 1955, holds the rank of hojatolislam, although some Iranian media reports refer to him as an ayatollah. Modarresi Yazdi has quickly become a favorite of current Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, with Khamenei appointing and reappointing him to the Guardian Council. He lost the election for membership in the Assembly of Experts in 2016.

Recently, before Ebrahim Raisi became chief justice, media reports indicated Modarresi Yazdi was on the shortlist to succeed Sadegh Larijani as judiciary chief. He’s been critical of clerics even supporting reformists in Tehran’s political life, speaking out against Grand Ayatollah Yousef Sanei for his support of Mir Hossein Mousavi during the Green Movement unrest of 2009.

Religiously, Modarresi Yazdi holds the requisite clerical ranking for the supreme leadership. Politically, he’s wounded because of his loss in the 2016 Assembly of Experts elections. However, administratively, the fact that Modarresi Yazdi’s candidacy was floated for the next chief justice of Iran, coupled with his longevity on the Guardian Council, makes him worthy of discussion for the post.

Mohammad-Mehdi Mirbagheri

Mohammad-Mehdi Mirbagheri, born in 1961 in the Shi’a city of Qom, rose to prominence in Iranian politics, particularly among conservative members of the Islamic Republic. Beginning his political journey in 2013, Mirbagheri aligned himself with figures like Saeed Jalili, marking his entry into the political arena. His subsequent role in the Assembly of Experts in 2015 further solidified his influence, where he became known for advocating staunch resistance against Western influence and promoting Islamic principles.

Mirbagheri’s ideological foundation, deeply rooted in his education under influential Shia clerics such as Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi, is a testament to the depth of his beliefs. His views on societal issues, particularly women and education, reflected traditional interpretations of Islamic teachings. He was noted for advocating compulsory hijab and critiquing Western educational models intended for Middle Eastern women. Mirbagheri’s perspective on global affairs was shaped by his belief in ‘Akhr al-Zaman’ (the End Times), framing current events as part of a larger cosmic struggle leading to the anticipated return of Imam Mahdi.

During an interview on Ofogh TV, Mirbagheri discussed various aspects of Islamic ideology and Iran’s geopolitical stance. He asserted that “Fighting in the cause of Allah’ constitutes an entirely moral war,” citing Quranic principles to support his perspective on armed conflict. Mirbagheri differentiated between negotiations intended to advance Islamic civilization, which he considered constructive as they could lead to ultimatums, and negotiations aimed at cooperating with non-Muslim societies, which he criticized. He expressed the Islamic Republic’s ongoing revolutionary commitment, arguing against integration into the international community under liberal democratic values and emphasizing the revolutionary spirit’s role in preparing for the Hidden Imam’s reappearance.

However, Mirbagheri’s tenure was subject to controversy and criticism. Critics often described him as radical and uncompromising, highlighting concerns over his alleged involvement in repressive measures and controversial statements on social issues. Despite calls from supporters within conservative factions for his leadership, Mirbagheri frequently declined, emphasizing his commitment to seminary work over political ambitions. This stance underscored a tension between his religious authority and aspirations within Iranian governance.

Throughout his career, Mohammad Mehdi Mirbagheri remained a divisive figure. His supporters respected him for his adherence to conservative Islamic principles, while detractors criticized him for what they perceived as restrictive policies.

Mirbagheri has the religious credentials to become supreme leader—as an ayatollah and Sayyed, or a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. He also has some degree of political standing as a member of the Assembly of Experts. But he lacks the necessary administrative skills and experience compared with other candidates and this will present a stumbling block. However, if powerful elements of the IRGC back him—and his radical beliefs suggest he could garner some support—he could be a puppet supreme leader, with the IRGC wielding real power behind the scenes.

Third Tier Candidates

Hassan Khomeini

Hassan Khomeini, born in 1972, is the grandson of the founder of the Islamic Revolution and first supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Hassan is the son of Ahmad Khomeini, who effectively served as chief of staff to his father during the Islamic Republic's nascent years. Following Ayatollah Khomeini’s death in 1989, Ahmad found himself sidelined. The Assembly of Experts had passed him over as a candidate for the supreme leadership—reports indicate Ahmad had wanted to succeed his father as supreme leader or at least be a member of a leadership council. In the years after his father’s death, Ahmad went on to become a custodian of Ruhollah Khomeini’s shrine and the supreme leader’s representative to the Supreme National Security Council.

After Ahmad died in 1995 from a heart attack, Hassan assumed control as custodian of Ruhollah Khomeini’s mausoleum. Iranian media reports indicate Hassan holds the rank of hojatolislam. Yet in 2016, when Hassan announced his candidacy for a seat on the Assembly of Experts, the Guardian Council barred him from running because his religious credentials could not be established due to his failure to participate in an examination. Some reports speculate his disqualification was due to his reformist leanings. At the time, Hassan wrote on Instagram, “All my support from top clerics has been ignored, as have been my religious publications.” In recent years, hardliners have also criticized Hassan Khomeini’s family for their extravagant lifestyle during a time of economic turmoil. Ahead of the 2021 presidential election, Hassan Khomeini’s name appeared on lists of potential candidates, including for the Executives of Reconstruction Party. However, reports later emerged that Iran’s supreme leader advised Khomeini against running for president in 2021, and he never registered his candidacy.

Religiously, while Iranian media technically refer to Hassan as a hojatolislam, the same rank that Ali Khamenei held before he ascended to the supreme leadership, the fact that the Guardian Council wouldn’t even bless his candidacy for a seat on the Assembly of Experts will hamper his candidacy for an even higher office. Politically, the Khomeini family has not had a role in the daily governance of the Islamic Republic in decades. However, Ruhollah Khomeini remains an enduring symbol as the founding father of the Islamic Republic. His family name, coupled with his standing among reformists, may make Hassan a topic of debate and discussion during a succession process. But opponents of his candidacy may point to Ruhollah Khomeini’s remarks from 1980 in which he said “I will that those who are related to me not enter political currents… I do order you based on Shariah not to enter political games.”

Administratively, Hassan Khomeini hasn’t overseen a branch of government or even served as a member of a state organ. This deficit stands in contrast to candidates like Mojtaba Khamenei, who serves as a trusted advisor to his father, and even Hassan’s father Ahmad, who served as aide-de-camp to Ruhollah Khomeini immediately prior to the 1989 succession. Thus, beyond symbolism, which is important, Hassan Khomeini lacks the confidence of many in the clerical establishment in addition to state management experience.

Ahmad Marvi

Ahmad Marvi, born in 1958 in Mashhad, Iran, emerged as a prominent figure deeply intertwined with the leadership of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. His upbringing and education laid the foundation for his influential role within Iran’s clerical hierarchy. Marvi underwent extensive theological training and studied under renowned scholars, including Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. This shaped his devotion to Shia Islam and his alignment with Khamenei’s teachings and directives. His educational background and religious credentials prepared him for significant responsibilities within the Iranian regime.

Before he was appointed custodian of Astan Quds Razavi (AQR) in April 2019, Marvi held pivotal positions within Khamenei’s office, overseeing contacts with religious seminaries and managing religious affairs. This experience solidified his stature within Iran’s religious establishment and underscored his loyalty and commitment to Khamenei’s leadership. Marvi’s appointment to AQR, tasked with overseeing operations at the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad, marked a significant elevation in his career, highlighting his close association with Khamenei and his trusted role within the regime.

Marvi’s leadership of AQR was not limited to religious stewardship. Under his direction, AQR underwent a significant transformation, evolving into a multifaceted entity with interests spanning construction, agriculture, energy, telecommunications, and financial services. This economic expansion was managed through AQR’s Razavi Economic Organization, which positioned Marvi at the intersection of religion and commerce. It also allowed him to exert considerable influence on Iran’s economic landscape under Khamenei’s oversight, demonstrating his ability to navigate the complex relationship between religion and commerce in Iran.

Beyond his administrative duties, Marvi is known for his staunch advocacy of Khamenei’s policies and ideologies, echoing the supreme leader’s positions on societal issues such as women’s rights and technology. He has publicly defended Khamenei’s image as a revered figure and upheld traditional Islamic values, opposing perceived Western influences on Iranian society. Marvi’s alignment with Khamenei’s worldview extends to geopolitical matters, where AQR’s activities have supported fundamentalist and terrorist groups connected with the Islamic Republic.

In January 2021, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned Ahmad Marvi under Executive Order 13876 for his role as the custodian of AQR, which is designated for being owned or controlled by the supreme leader of Iran.

Ahmad Marvi’s experience at AQR provides bureaucratic, financial, and religious heft to his candidacy to succeed Khamenei. His closeness to Khamenei also may enhance his chances. However, his lack of name recognition and considerable governmental administrative experience will hamper his stock.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox

The Iran nuclear deal is done. And the world's biggest companies have already visited Tehran ready to strike a deal when sanctions end. These businesses will add even more to Iran's bottom line. And that means continued development of nuclear technologies and more cash for Hamas and Hezbollah.