Organizational Chart of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Office of the President

In theory, the presidency is often described as the second-highest official—the ultimate authority is the supreme leader—in the Islamic Republic. According to the constitution, the president is responsible for national planning, budget, and state employment affairs; has the authority to sign treaties, protocols, contracts, and agreements concluded by the Iranian government with other governments and international organizations after approval by the parliament; is required to sign legislation after it has been approved by the requisite bodies; has the authority to sign and receive the credentials of ambassadors; nominates cabinet ministers, which are subject to confirmation by the Iranian parliament; appoints vice presidents; and serves as chairman of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC). However, in practice, other power centers in the Iranian establishment outrank the presidency in their control over state affairs, most especially the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) with respect to Iran’s regional policies. While the president does have the opportunity to nominate cabinet ministers, the most sensitive ministerial roles, like foreign affairs, intelligence, and defense, are subject to the preapproval of the supreme leader. This is not to mention that the president is not the commander-in-chief—that authority lies with the supreme leader. The Law Enforcement Forces of the Islamic Republic (LEF) function as the national police force and report formally to the Interior Ministry, which in turn reports to the president, but the supreme leader directly names the LEF commander, who is usually an IRGC officer.

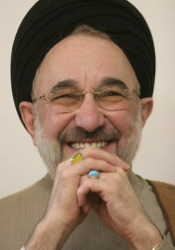

Since Ayatollah Ali Khamenei ascended to the supreme leadership in 1989, the Islamic Republic’s presidents—with two exceptions—have presented a more acceptable face to the world to mask the darker nature of the Iranian regime. Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani were two such presidents. But Khatami’s presidency was undermined by the supreme leader’s consolidation of authority and conservatives’ relentless attacks against his administration, which proposed a dialogue among civilizations. Rouhani entered office with international experience and exposure, but the failure of the Iran nuclear deal to deliver on his watch damaged his presidency. The two international outcasts who occupied the presidency were Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, whose incendiary rhetoric and Holocaust denial made it easier to marshal support for isolating Tehran, and Ebrahim Raisi, whose own bloodstained record as a member of a death commission in the 1980s which greenlighted the execution of thousands of political dissidents has further tarnished the regime on the world stage. Nevertheless, Iran’s supreme leader, despite the presidency, remains the final decision-maker in the Islamic Republic. While the president nominally chairs the SNSC and can have input in debates of state, he is not the ultimate decision-maker on foreign and nuclear policy. Some observers describe the Office of the President as akin to a chief operating officer. After the death of Raisi in a helicopter crash, Mohammad Mokhber, the former head of the economic conglomerate the Execution of Imam Khomeini’s Order and Raisi’s first vice president, is interim president.