The “pattern of penetration” enumerated in the previous section can be observed concretely by tracing the trajectory of Mohsen Rabbani, the chief architect of Iran’s Latin American missionary network aimed at exporting the Islamic Revolution. Iran’s ideological penetration of Latin America began in earnest in 1983, when it dispatched Rabbani “a young cleric with impeccable revolutionary credentials” to Buenos Aires. During his 14-year posting, Rabbani was the pivotal figure in the nexus between Iran’s religious and cultural, diplomatic, and terroristic activities in Latin America, travelling extensively throughout the region in an effort to replicate the model he perfected in Argentina.

The impetus for Rabbani’s arrival in the region occurred a year prior, during a 1982 international conference in Tehran, which Nisman identified as the “turning point for the regime’s method to export the [Islamic] Revolution.” According to Nisman, former IRGC commander Javad Mansouri addressed the conference, stating, “Our revolution can only be exported with grenades and explosives.” Nisman further contends that “Javad Mansouri called to turn each Iranian embassy into an intelligence center and a base to export the revolution” during his speech. By the conclusion of the conference, Iran arrived at the fateful decision to spread its ideology through subversive violence and terrorism. Several months later, Rabbani, who “was not just any operative, but one of Iran's most highly trained and dedicated intelligence officers,” arrived in Buenos Aires and set about operationalizing Iran’s push into Latin America following the blueprint laid out by Mansouri.

Although he came to Buenos Aires on a tourist visa, Rabbani initially set up shop as a representative of the Iranian Ministry of Meat. His true mission, however, was to proselytize and radicalize the local Shi’a community, which was growing at the time as large numbers of Lebanese refugees emigrated to South America to escape the civil war. By his own admission, Rabbani was dispatched to Argentina “in order to create support groups for exporting the Islamic revolution.” Argentine prosecutors found that, “the driving force behind these efforts [to establish an Iranian intelligence network in Argentina] was Sheik Mohsen Rabbani. … From the time of his arrival in the country in 1983, Mr. Rabbani began laying the groundwork that allowed for the later implementation and further development of the [Iranian] spy network.” Years later, in a 2015 interview, he would claim that he travelled to the region at the “encouragement and guidance” of Ayatollah Khomeini himself.

Rabbani conducted his Latin America outreach efforts on behalf of Iran’s Islamic Propaganda Organization, which according to Nisman was charged with identifying groups and individuals sympathetic to Iran’s terroristic machinations to export its revolution. In an early missive sent to his backers in Tehran, Rabbani underscored his subversive intent, writing, “According to our Islamic point of view, Latin America is for us and the international world, a virgin area, that unfortunately, till now, its huge potential has not been taken into account by the Islamic people of Iran. (…) we have a solid support against the imperialism and Zionism intrigues, being an important aid in favor of our presence in the area.

After an initial nine-month visit, Rabbani returned to Iran and began working for the AhlulBayt World Assembly, an internationally-active Iranian NGO tasked with disseminating Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolutionary Islamist ideology around the world. Rabbani urged his superiors and Iranian officials to enhance their activities in the region, and ultimately, he was tasked with spearheading Iran’s outreach due to the familiarity and contacts he had now amassed.

Upon his return, Rabbani centered his efforts at the At-Tauhid mosque, where he taught religion and rose to become the mosque’s leader by 1987. Argentina’s National Land Registry showed that the At-Tauhid mosque was owned by the government of Iran, and its operating expenses were covered by the Iranian embassy in Buenos Aires. Rabbani used his vaunted position as imam at At-Tauhid to propagandize and recruit on behalf of the Islamic Revolution, creating “an intelligence system that would report to the Iranian Embassy in Buenos Aires and then up to Tehran.” Rabbani also used at-Tauhid as a base to coordinate revolutionary activities across Latin America, travelling extensively throughout the region on educational and indoctrination missions and disbursing funds to mosques and cultural centers for similar proselytization purposes.

Now firmly embedded in Buenos Aires’ Shi’a community, Rabbani gained a reputation as a “spokesman of the hardest line inside the Iranian regime,” according to the summary of Nisman’s 2013 500-page indictment report. Three of his former students later testified that in 1990, Rabbani had urged them “to export the revolution” and declared “we are all Hezbollah.” In 1991, Rabbani addressed an audience of Argentinean right-wing activists and local Shi’a at a convention hall and insisted in rudimentary Spanish, “Israel must disappear from the face of the earth.”

As his radical rhetoric escalated in the early 1990s, Rabbani’s explicit ties to terrorism also crystallized. The intelligence network he had labored to create was firmly ensconced, enabling Iran to provide logistical support for terrorist attacks in South America. Rabbani took on a leadership role in Hezbollah’s operational activities on the continent, and is alleged to have scouted targets for the terrorist movement in the run-up to the first major Iran-linked terror attack in South America, the bombing of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires on March 17, 1992.

The Israeli embassy bombing was carried out by a suicide terrorist who detonated a truck carrying 220 pounds of explosives, killing 29 and wounding 292. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) conducted an investigation into the attack in conjunction with the Counter Terrorism Center, and concluded that Hezbollah operatives Imad Mughniyeh—one of the organization’s senior-most operatives and the chief perpetrator behind the 1983 bombing of the U.S. embassy in Beirut—and Talal Hamiyah were the principal planners, and that Hezbollah carried out the attack at Iran’s behest, but took on all operational aspects to shield Tehran from direct involvement.

American, Argentinian, and Israeli investigators all independently found that funding for the attack came from sympathetic elements of the Shi’a community in the TBA between Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil, and that the perpetrators hailed from this region as well. According to Dr. Matthew Levitt of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, “The investigation also began to reveal the central role Rabbani had in Hezbollah’s Latin American operations. Two weeks after the bombing, on April 3, 1992, Rabbani placed a call from his home phone to the secretary of Sheikh Fadlallah, a Lebanese Shi’ite religious leader with close ties to Hezbollah. Argentine intelligence detected the call and prosecutors pointed to it as timely evidence, not only of his relationship with Hezbollah, but of the leadership role he played in their operations.”

Less than two years after the attack on the Israeli Embassy, as investigators were still in the process of piecing together what had happened, Iran carried out another bombing targeting Buenos Aires’ Jewish community. On the morning of July 18, 1994, a Hezbollah operative detonated a suicide car bomb laden with 300-400 kilograms of explosives in front of the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA) Jewish community center, killing 85 and wounding over 200.

Nisman’s 2013 indictment report fingered Mohsen Rabbani, who had built a network of “local clandestine intelligence stations designed to sponsor, foster and execute terrorist attacks,” as the mastermind behind the attack. Nisman’s report further concluded that “the decision to carry out the AMIA attack was made, and the attack was orchestrated, by the highest officials of the Islamic Republic of Iran at the time, and that these officials instructed Lebanese Hezbollah – a group that has historically been subordinated to the economic and political interests of the Tehran regime – to carry out the attack.”

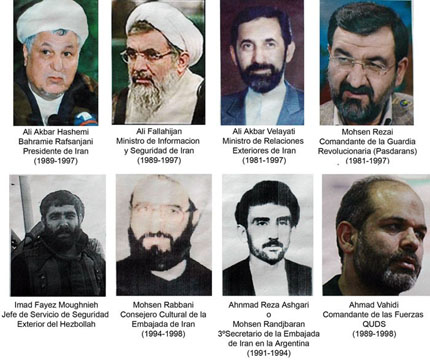

In the intervening period between the two major terrorist attacks, Rabbani traveled back-and-forth to Iran on several occasions. On one of these visits in August 1993, he attended a meeting in Mashad of senior regime officials including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Minister of Intelligence Ali Fallahian, Foreign Minister Ali Velayeti, and Ahmad Asghari, a suspected IRGC official stationed at the Iranian embassy in Buenos Aires. It was at this meeting that the decision to bomb AMIA was made based on the scouting reports of potential American and Jewish targets compiled by Rabbani and his spy network. Argentine intelligence found that Supreme Leader Khamenei himself went so far as to issue a fatwa sanctifying the operation as a fulfillment of Iran’s revolutionary objectives.

Once the decision to attack AMIA was made, Imad Mughniyeh was placed in charge of the operational aspects of executing the attack, which he conducted from the Argentina-Paraguay-Brazil TBA, while Rabbani handled local logistics, “including all details pertaining to the purchase, hiding, and arming of the van to be used in the bombing, and liaising with the Hezbollah operatives on the ground in Argentina.” Rabbani would travel to Iran once again in February 1994, whereupon he was newly credentialed as the Cultural Attaché to the Iranian Embassy in Buenos Aires, and accordingly granted a diplomatic passport. This hasty appointment enabled Rabbani to use the cover of the Iranian embassy “to go about providing material support for the operation with relative ease, while at the same time guaranteeing him diplomatic immunity following the attack.“ An FBI investigation into the attack found that Rabbani used his perch in the office of the Cultural Attaché to stay in frequent contact with the embedded Hezbollah operatives in the TBA. Their report alleged that “in the months prior to the attack, there were many calls from the mosque in the city of Iguaçu Falls (in the TBA) to Iran, the Embassy of Iran in Buenos Aires, the Embassy of Iran in Brasilia, the at-Tauhid mosque in Buenos Aires, and the office of the cultural attaché where Rabbani worked.”

The initial Argentinean investigation into the AMIA bombing was plagued by irregularities and limited in scope, eventually assigning culpability to “a small group of fanatics that served as a shield for an Islamic fundamentalist group that presumably had ties to Hezbollah.” Finally, by 2005, the original prosecutor was impeached and replaced by Alberto Nisman, who restarted the investigation from scratch. Nisman’s dogged pursuit of justice led to the conclusion in 2006 “that the decision to carry out the attack was made not by a small splinter group of extremist Islamic officials, but was instead a decision that was extensively discussed and was ultimately adopted by a consensus at the highest levels of the Iranian government.”

Nisman’s findings precipitated the issuance by an Argentinean court of international arrest warrants for nine high-ranking Iranian and Hezbollah officials, former Iranian President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, senior Hezbollah operative Imad Mughniyeh, former Iranian Intelligence Minister Ali Fallahian, suspected IRGC official Ahmad Reza Asghari, former Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati, former Quds Force founder and commander Ahmad Vahidi, former IRGC commander Mohsen Rezai, former ambassador to Argentina Hadi Soleimanpour, and Mohsen Rabbani. Interpol subsequently issued Red Notices for the arrest of six of the alleged conspirators, declining to pursue charges against Rafsanjani, Velayati, and Soleimanpour. All of the alleged conspirators have eluded justice, with many maintaining positions of prominence in Iran. For instance, Ahmad Vahidi served as Ahmadinejad’s defense minister and currently serves as Interior Minister in the Raisi administration, while Velayati is the chief foreign affairs advisor to the Supreme Leader. Velayati and Rezai were both among the Supreme Leader’s approved shortlist of presidential candidates during the 2013 elections.

Iran’s relations with Argentina were severely damaged following the attack, until 2007 when Iran leveraged its ties with Venezuela to secure a rapprochement with Argentina. A March 2015 bombshell report in the Brazilian magazine, Veja, exposed a plot wherein Iran, using Venezuela as an intermediary, funneled cash to the election campaign of Christina Kirchner in exchange for technical knowledge of Argentina’s nuclear program (specifically, its heavy water reactor which was similar to Iran’s Arak reactor), and impunity for the AMIA attack. In 2011, President Kirchner went so far as to strike a deal with Iran to form a “truth commission” to verify Nisman’s findings, a highly dubious arrangement which in effect placed the alleged perpetrators of the attack in charge of investigating themselves. Nisman filed charges against Kirchner and Argentina’s foreign minister, Hector Timerman, for orchestrating a cover-up of Iran and Hezbollah’s role in the attack, but the day before he was set to present his findings to the Argentine parliament, he was found dead in his apartment under mysterious circumstances.